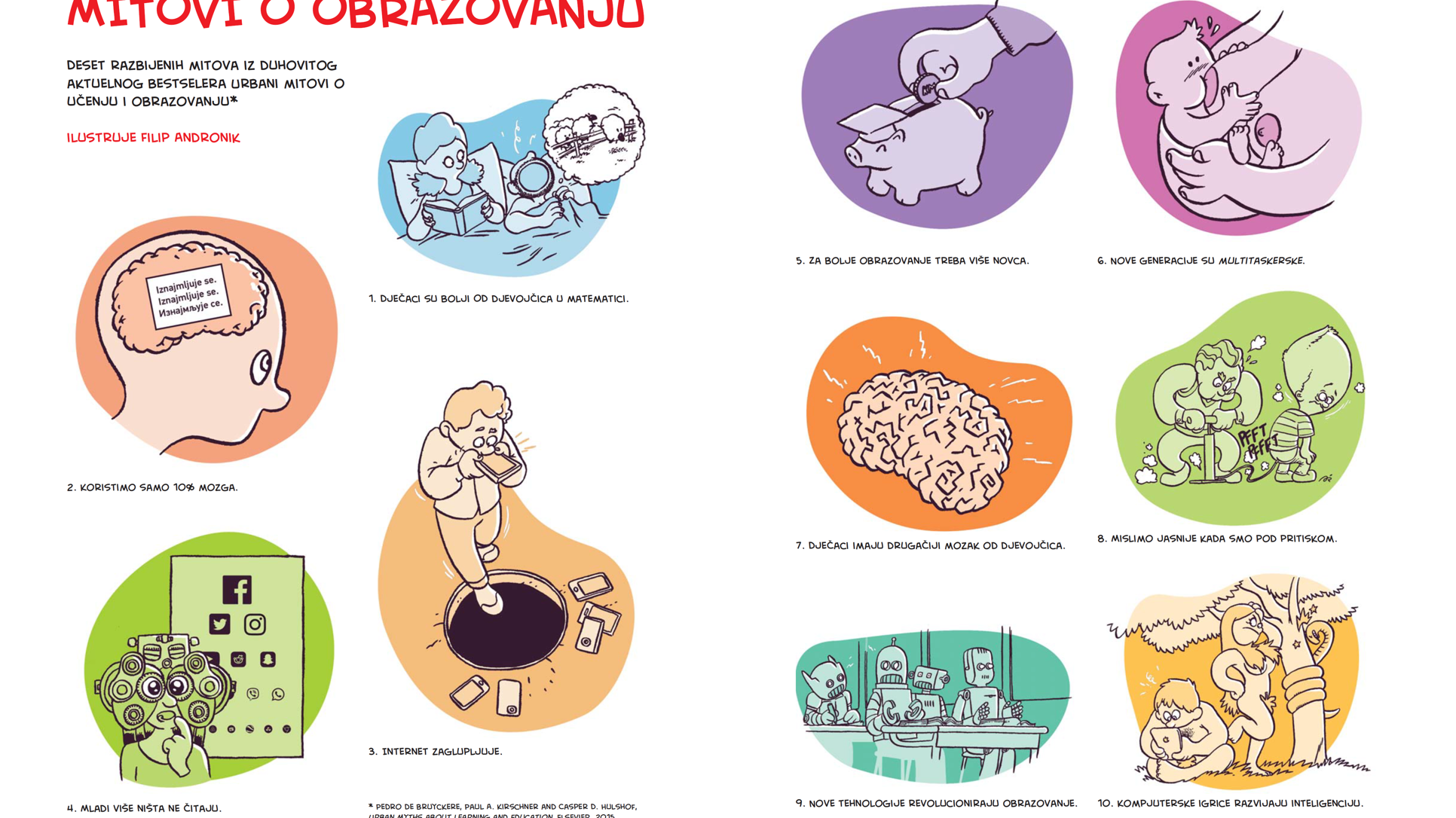

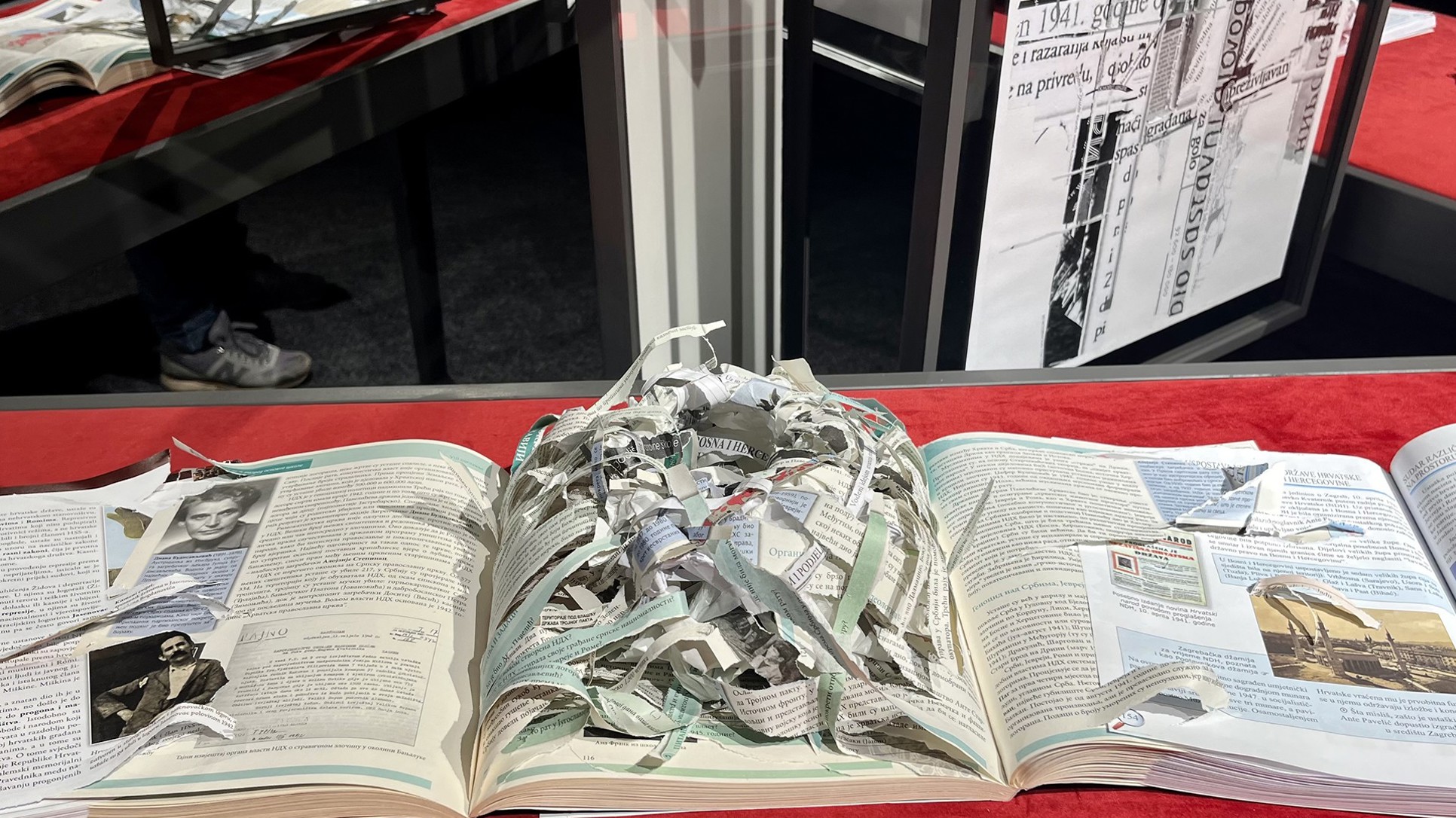

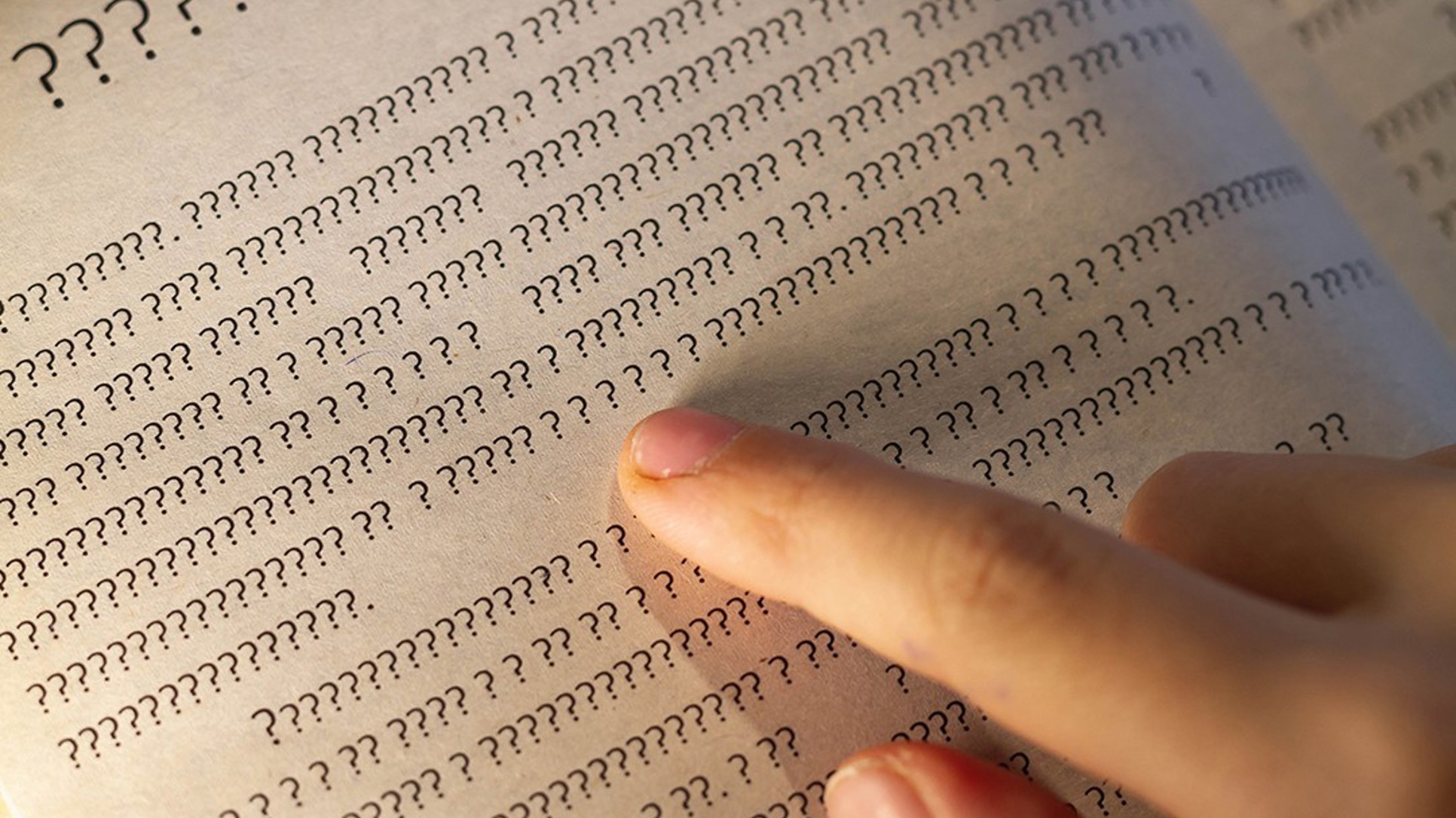

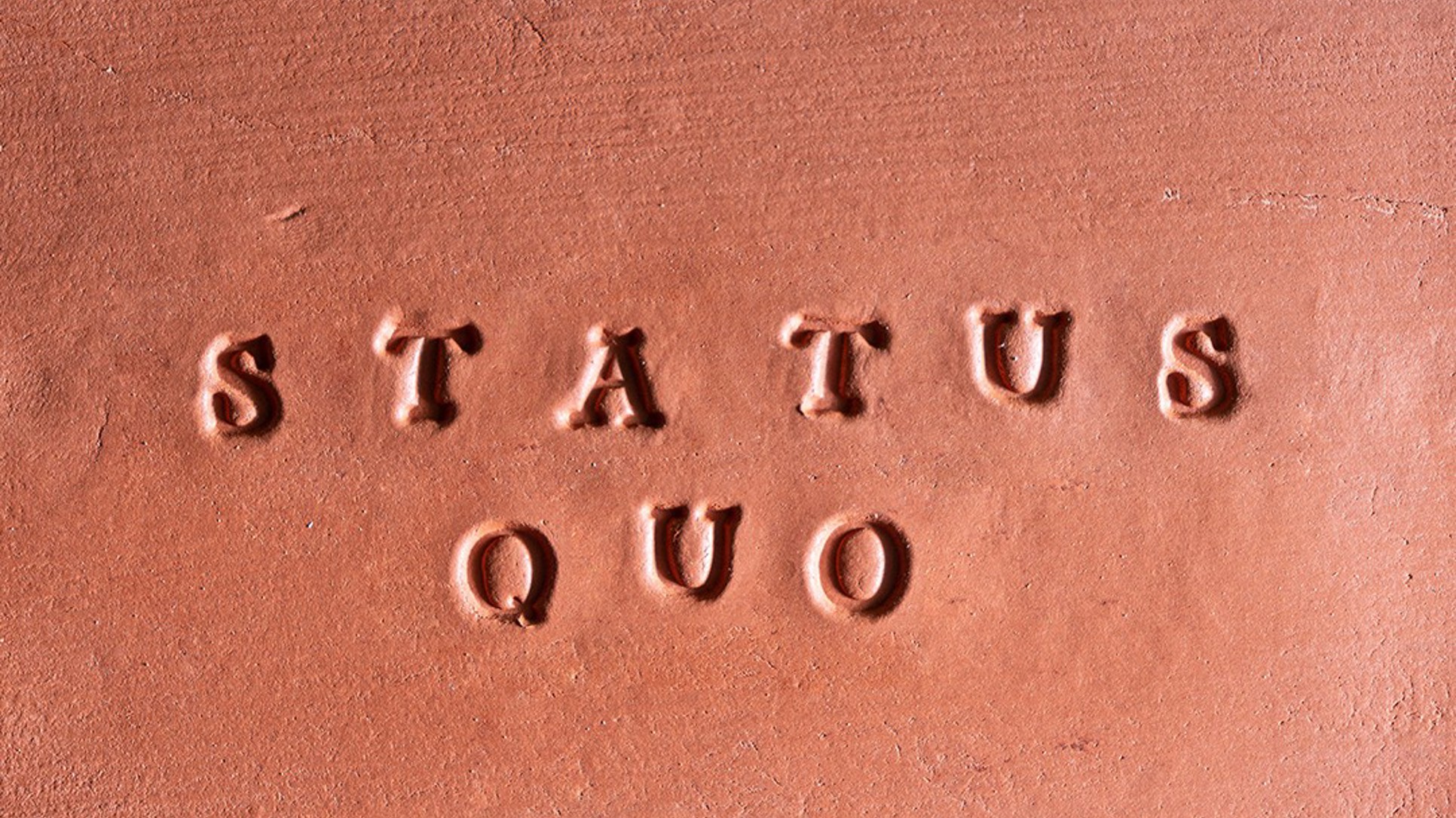

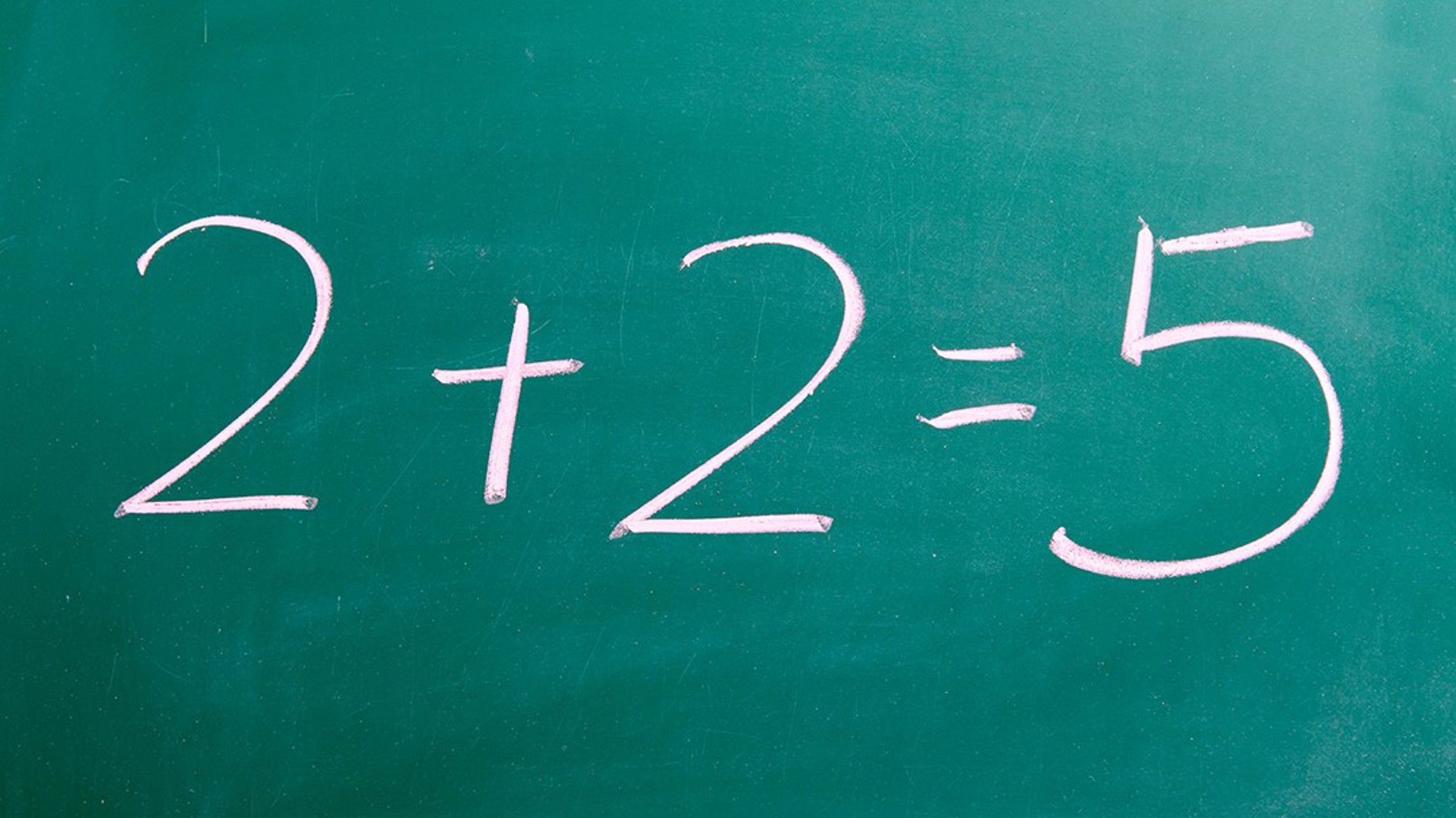

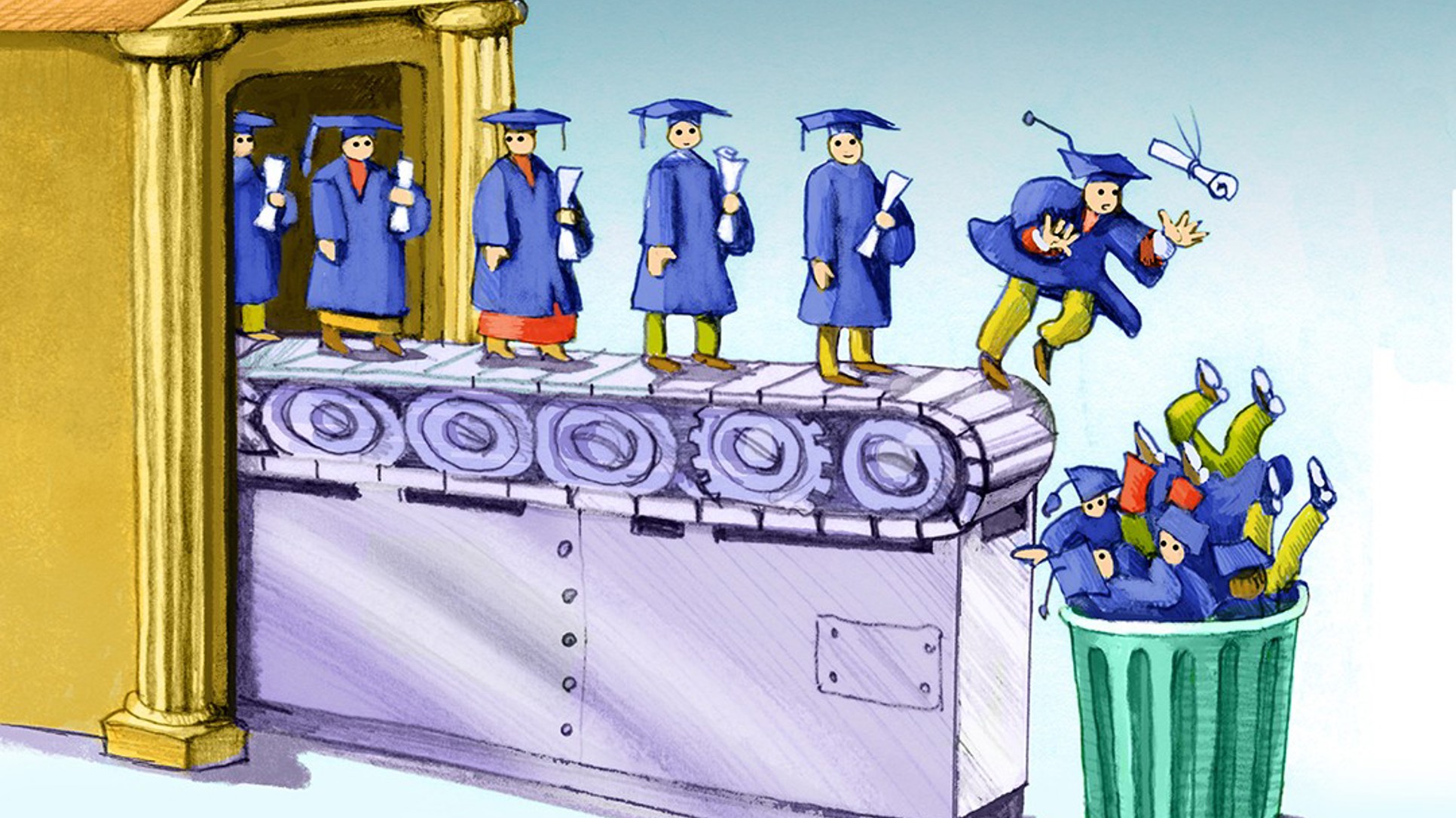

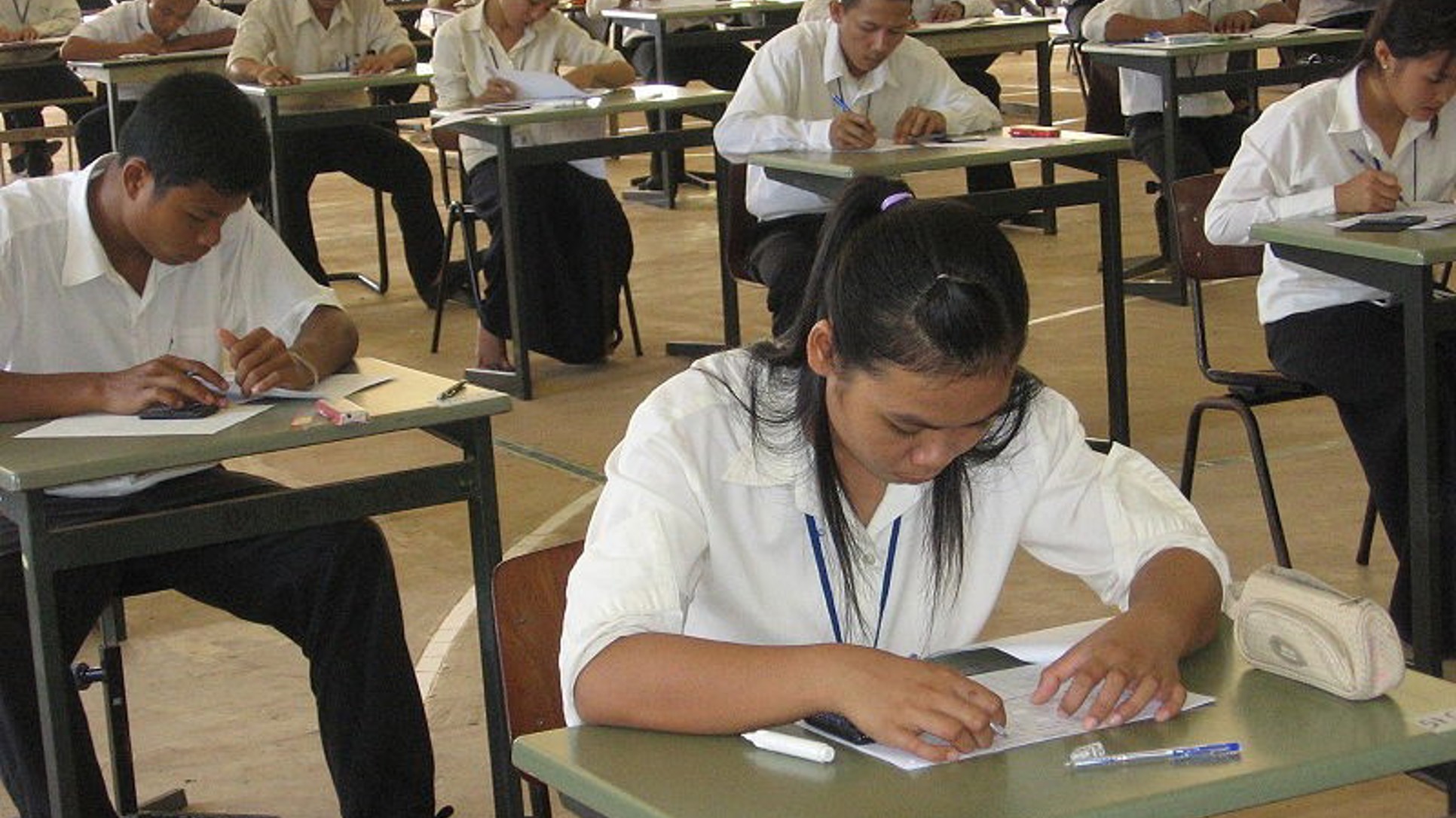

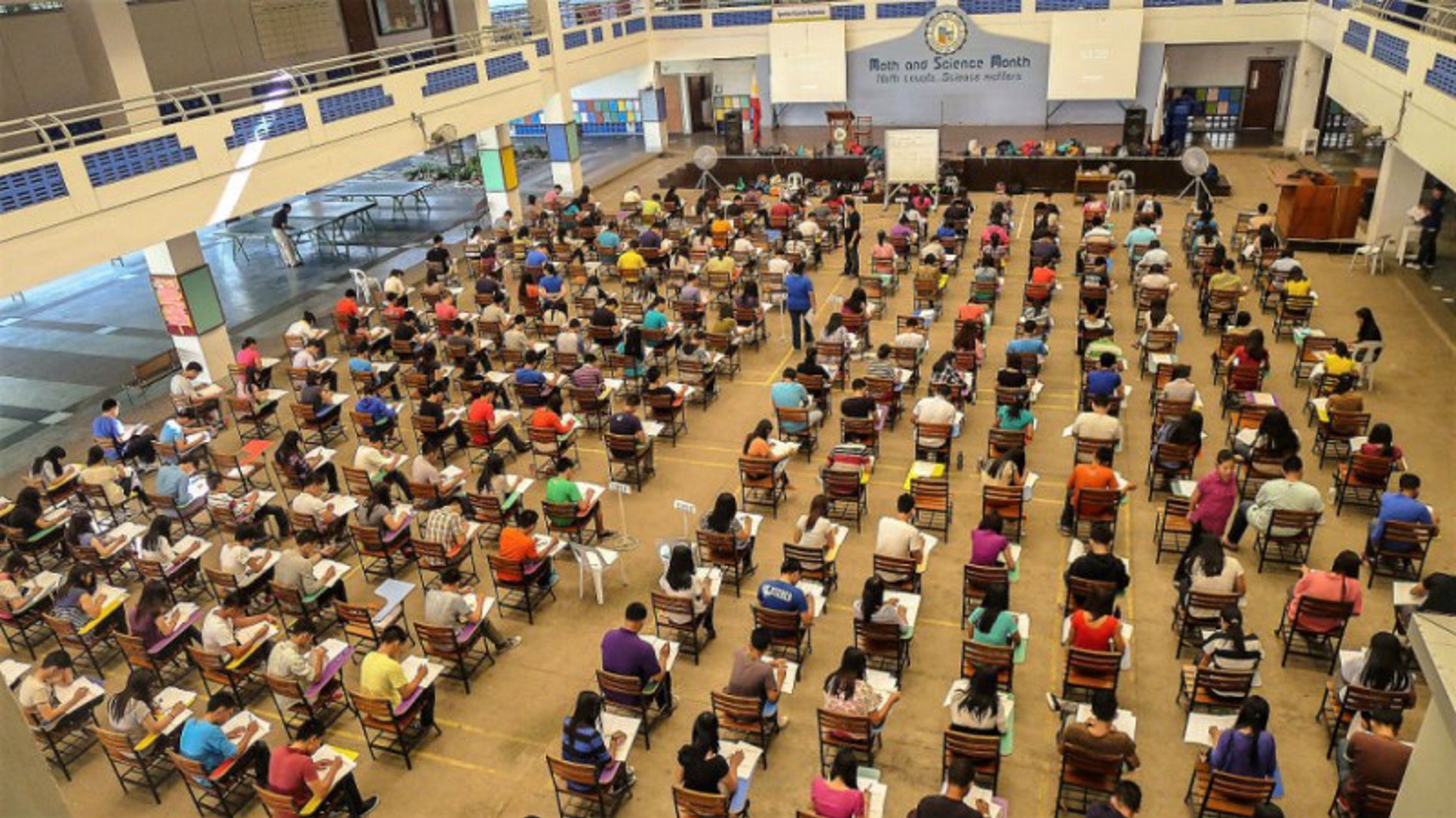

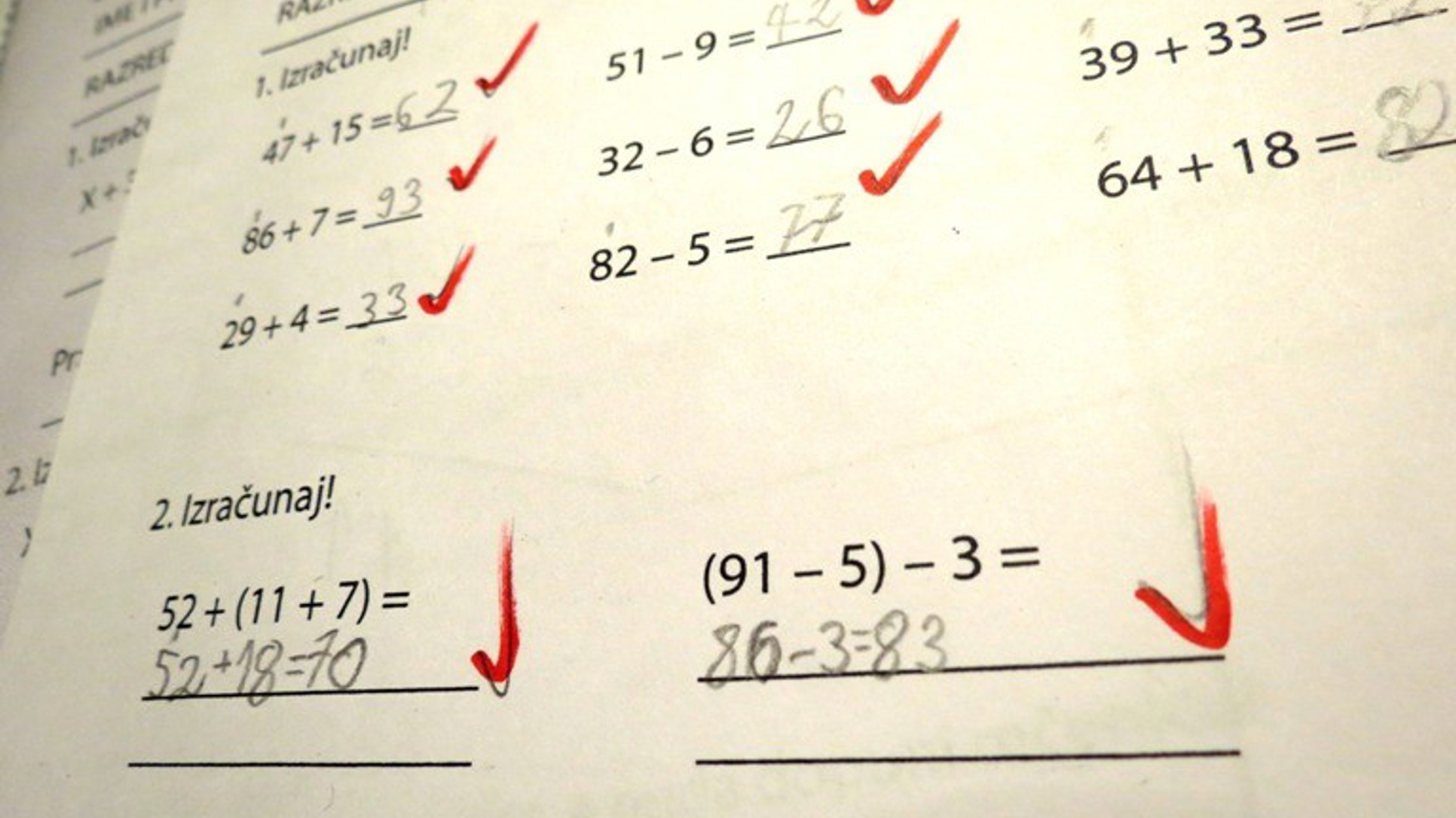

Recently, we have been talking about the "crisis in education", and we have the information that 50 percent of children around the world do not know how to distinguish what is fact and what is opinion - how did we get there, was it determined where we made a wrong step or started making wrong ones steps?

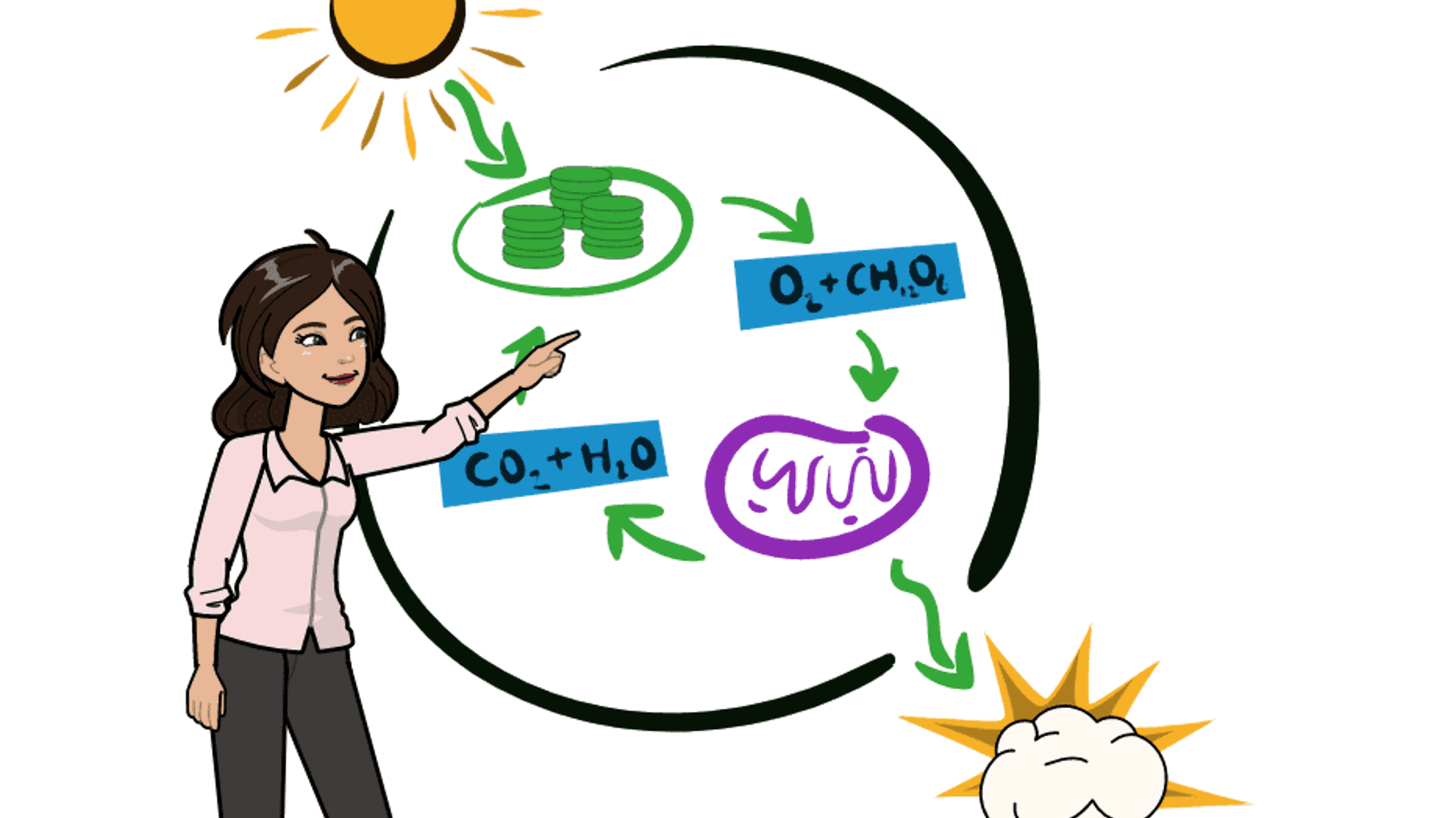

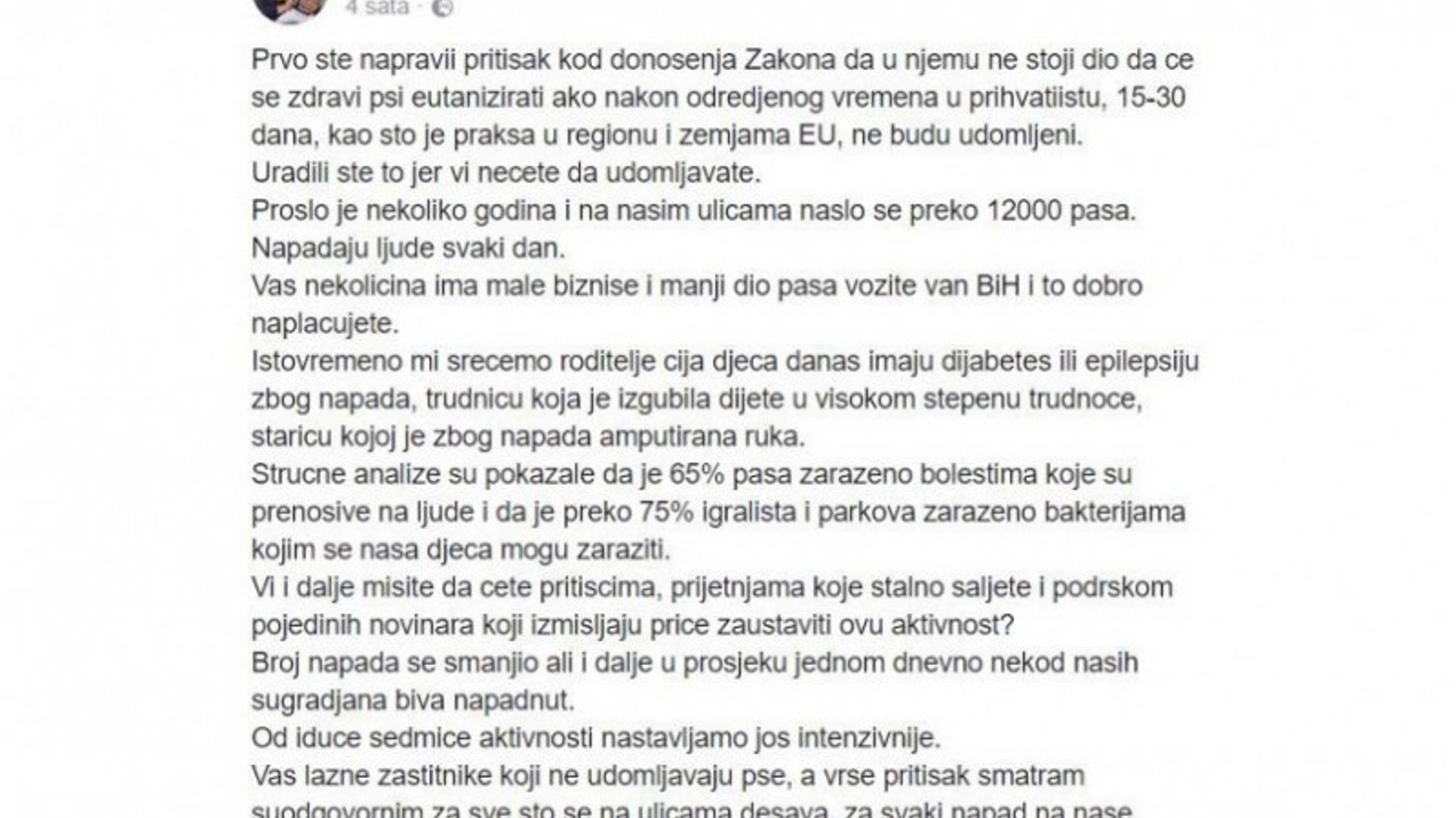

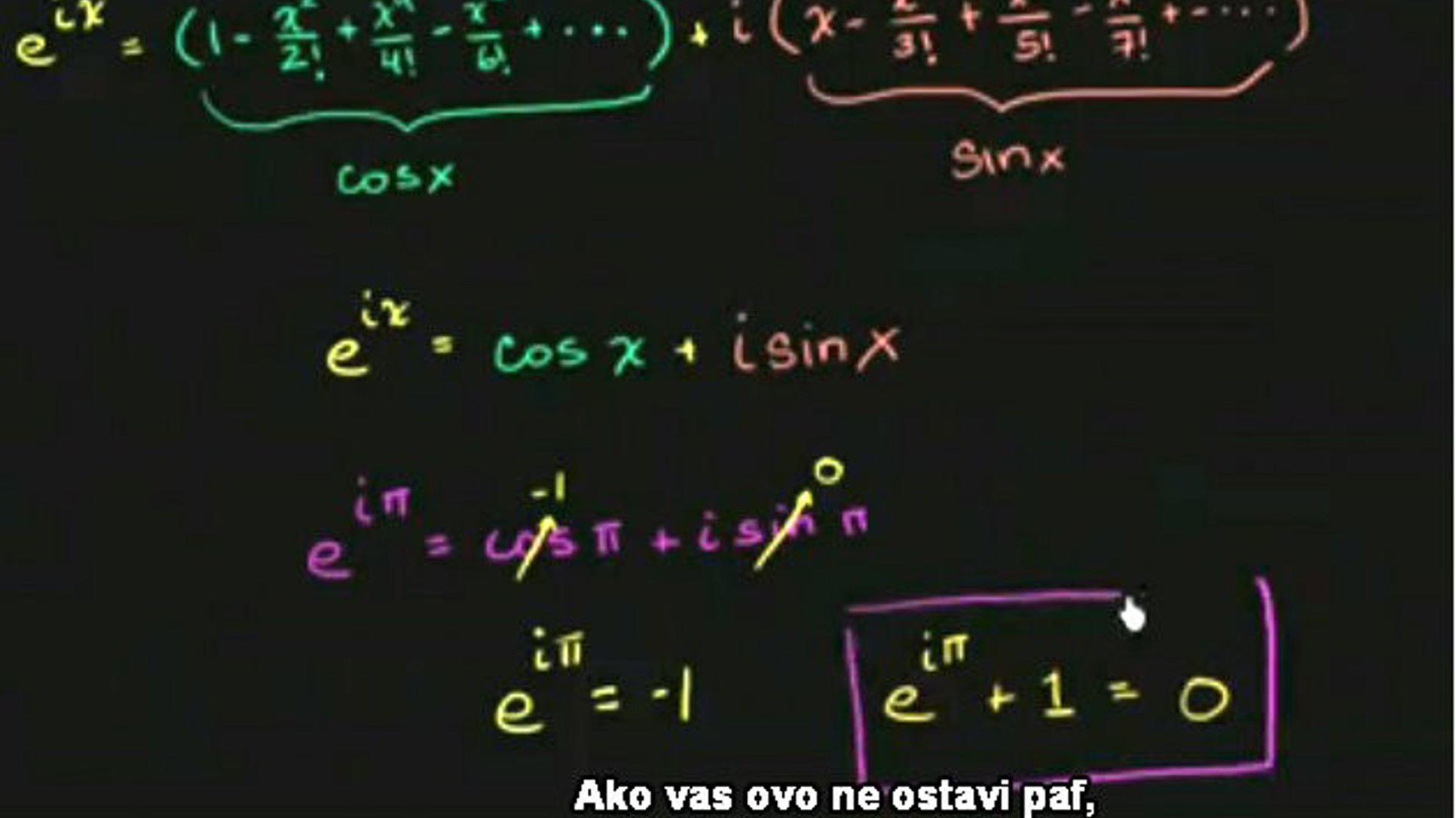

Standardised evaluations that assess whether students are able to distinguish fact from opinions are recent, so it is difficult to evaluate how the mastery of this skill has evolved in the student population over years – let alone to explain “how we got there”. What we know has changed, however, is the media environment. Today, with the multiplication of sources of information, the rise of social media that have turned us all into authors and publishers, and the change of people’s habits in communication, it appears that reading a piece of information more than ever requires evaluating the quality and validity of different sources, navigating through ambiguity, checking biases, distinguishing between fact and opinion, to ultimately construct knowledge.

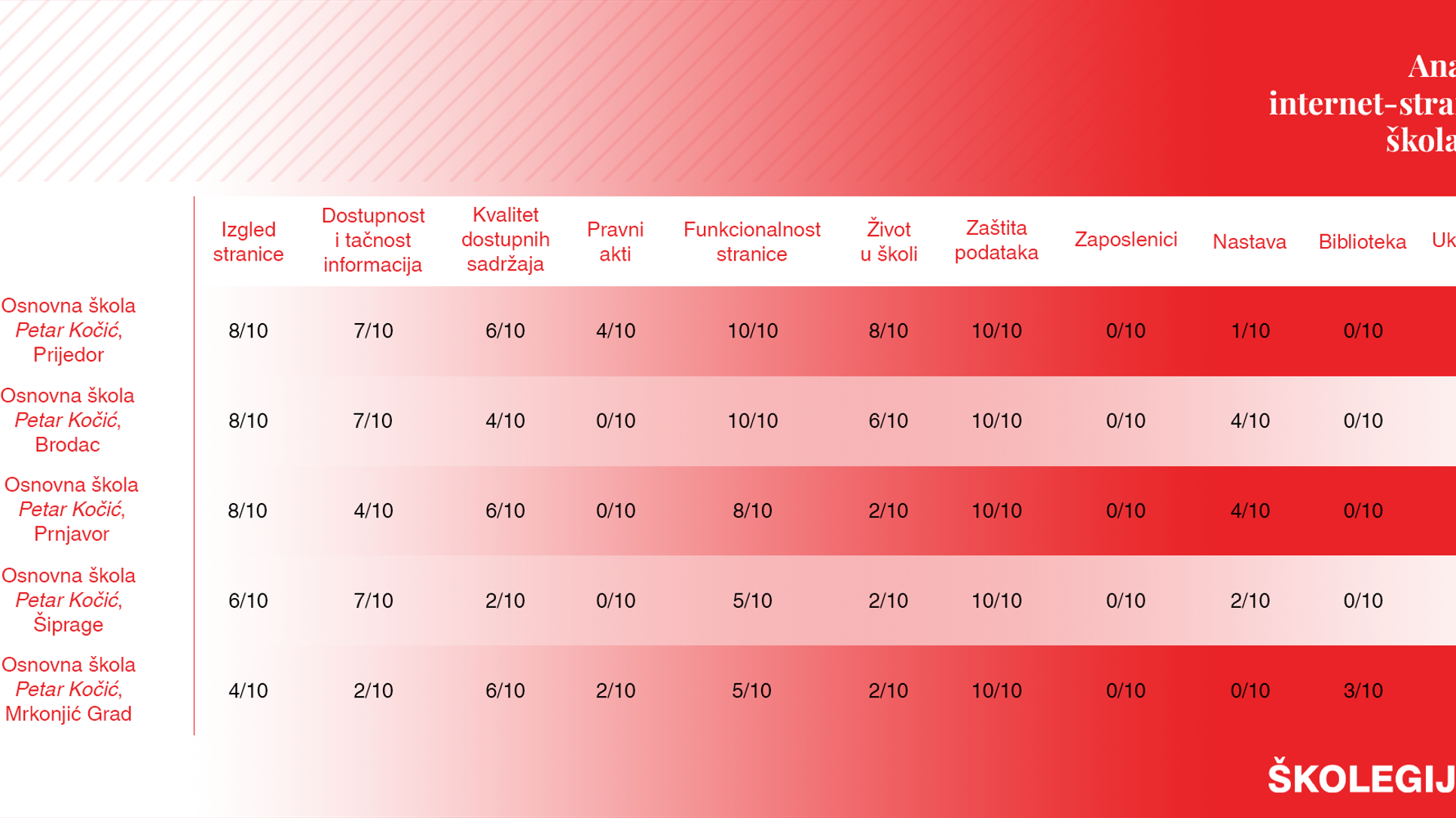

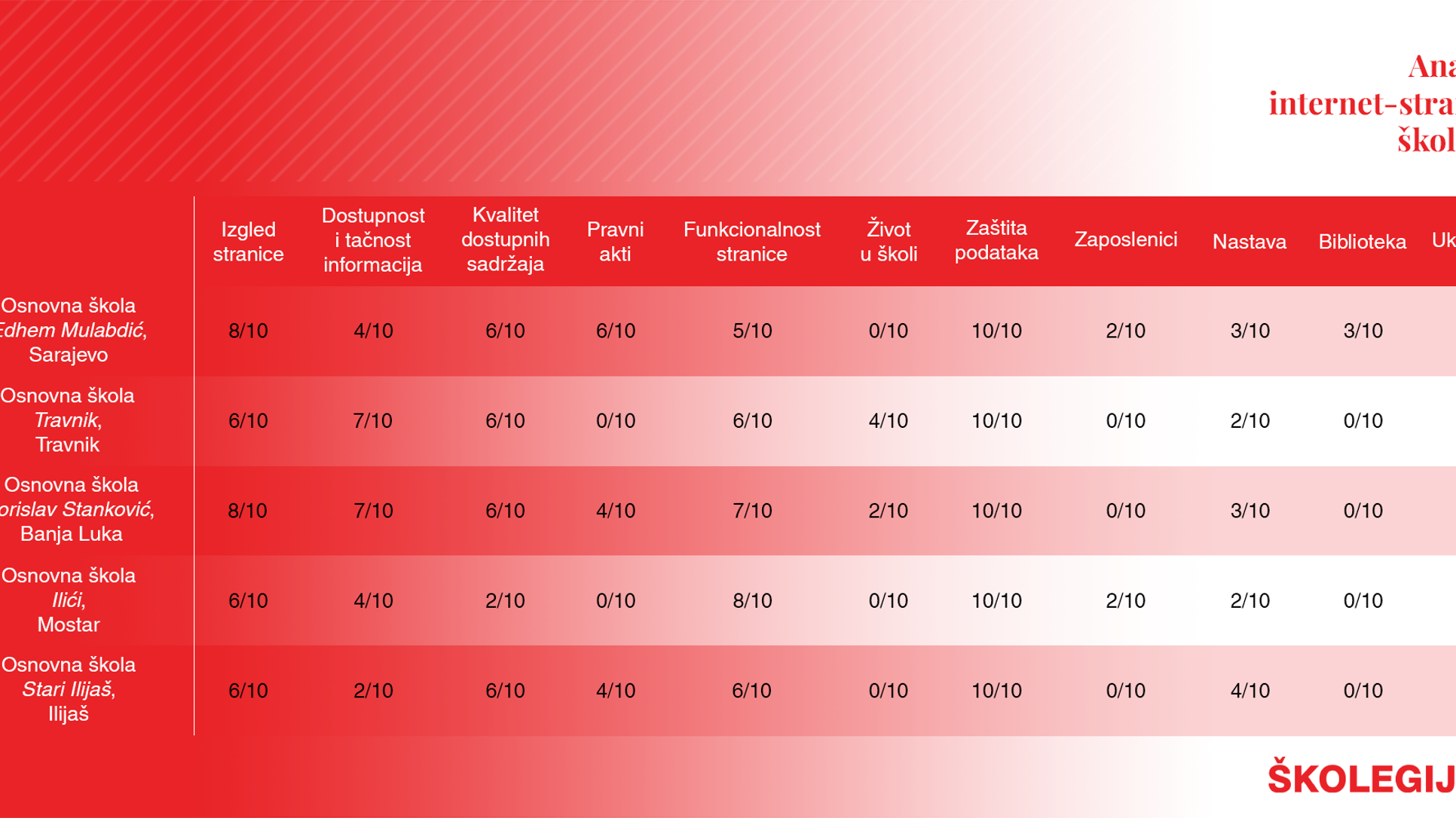

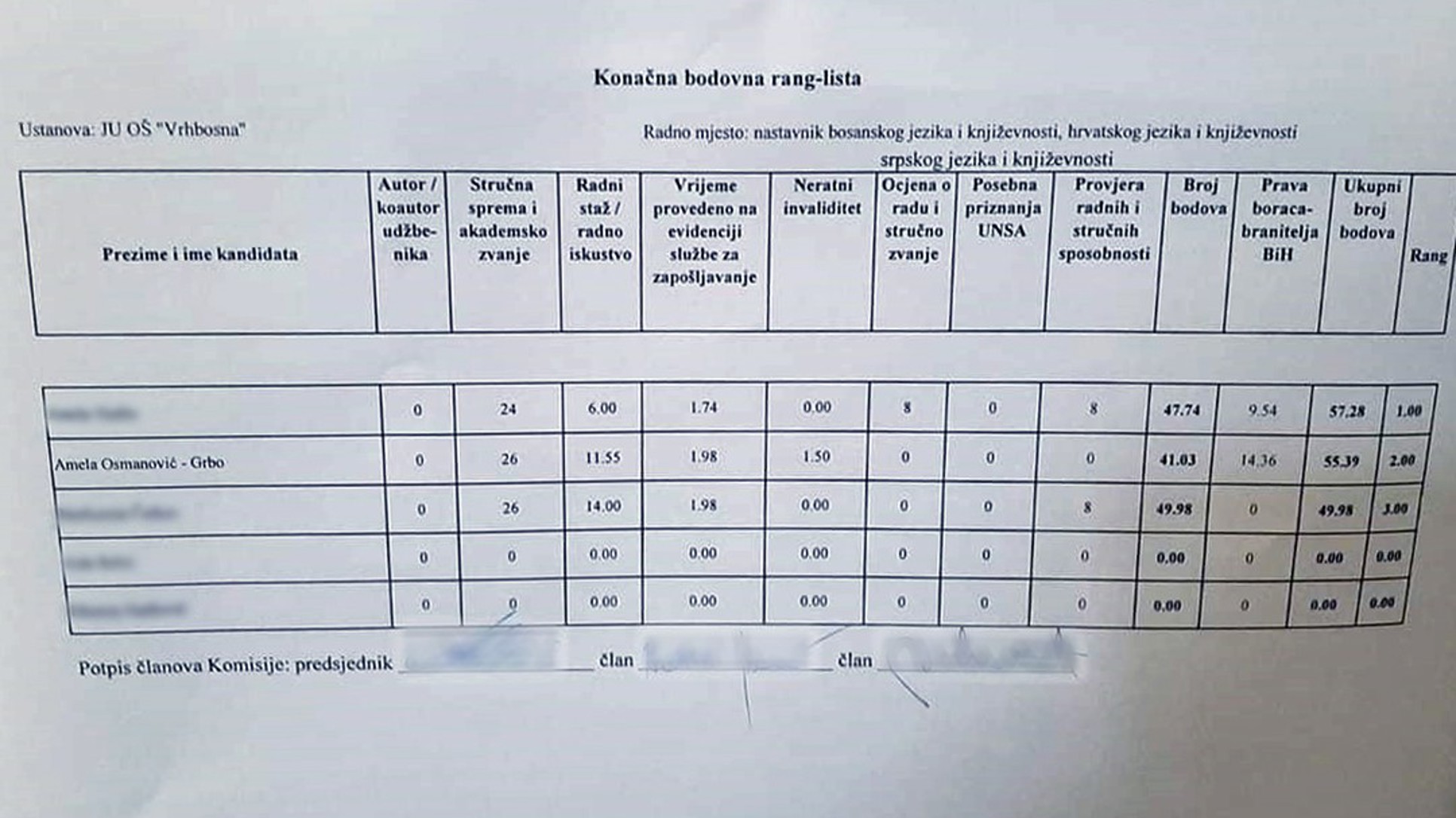

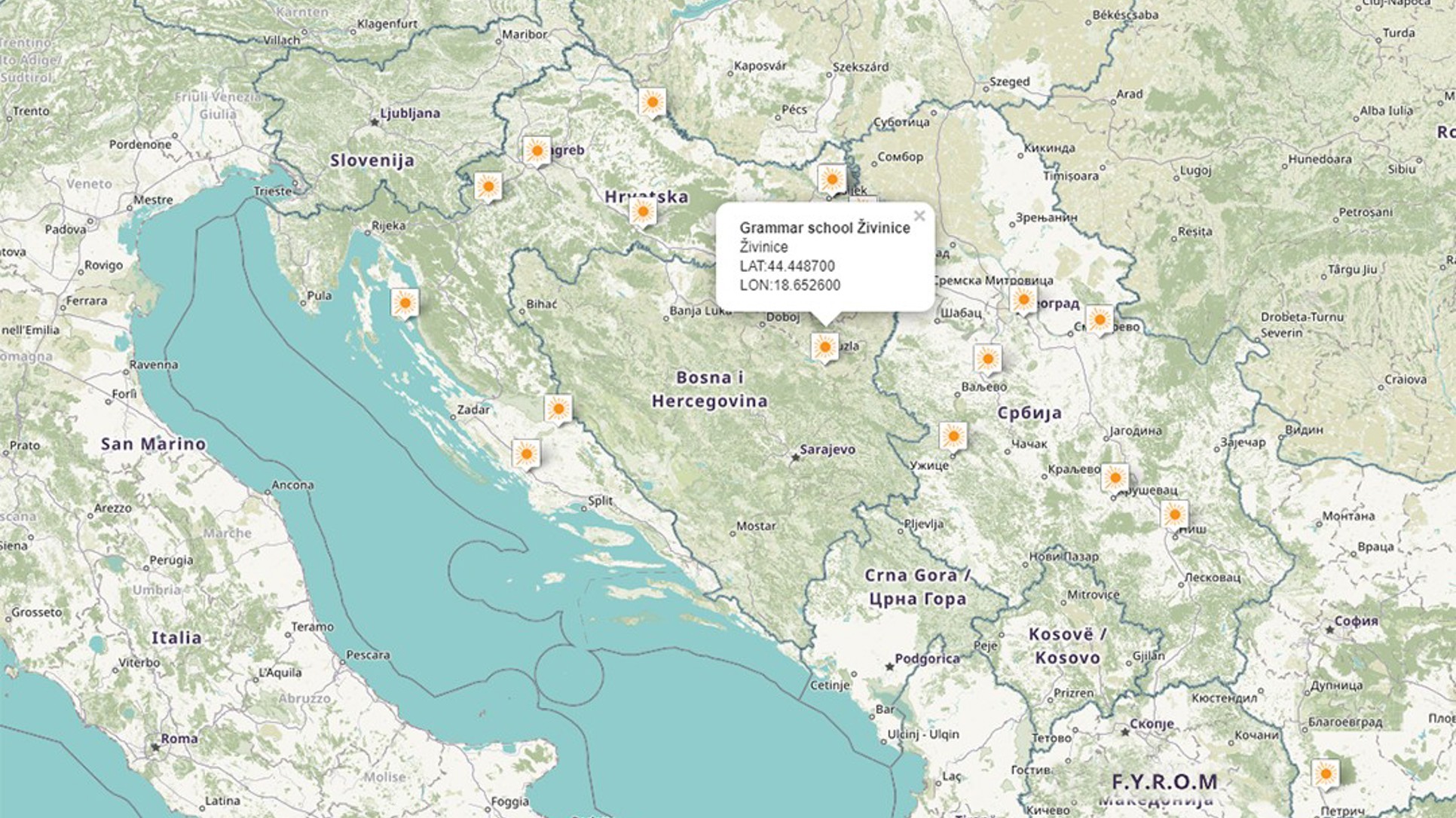

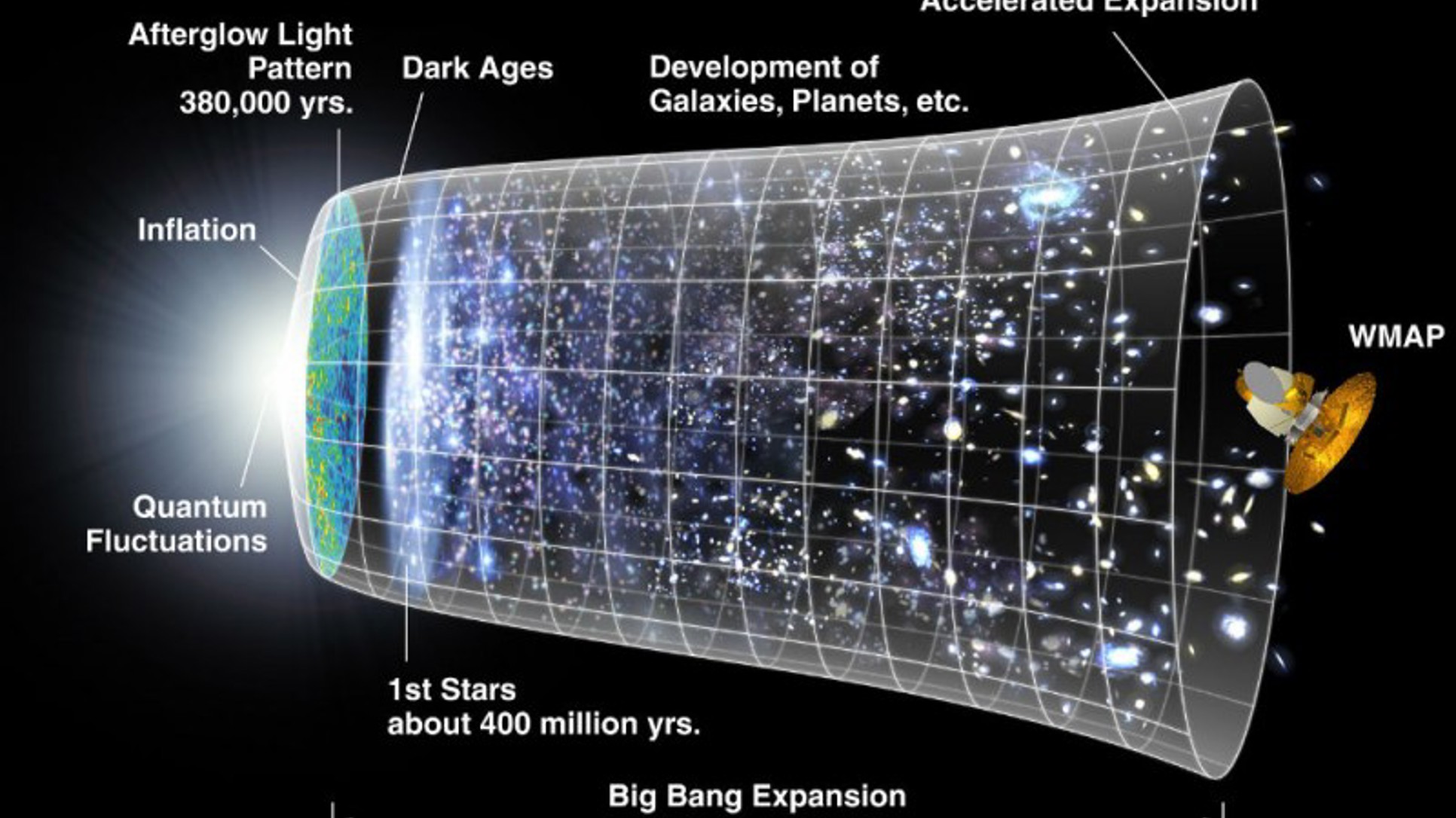

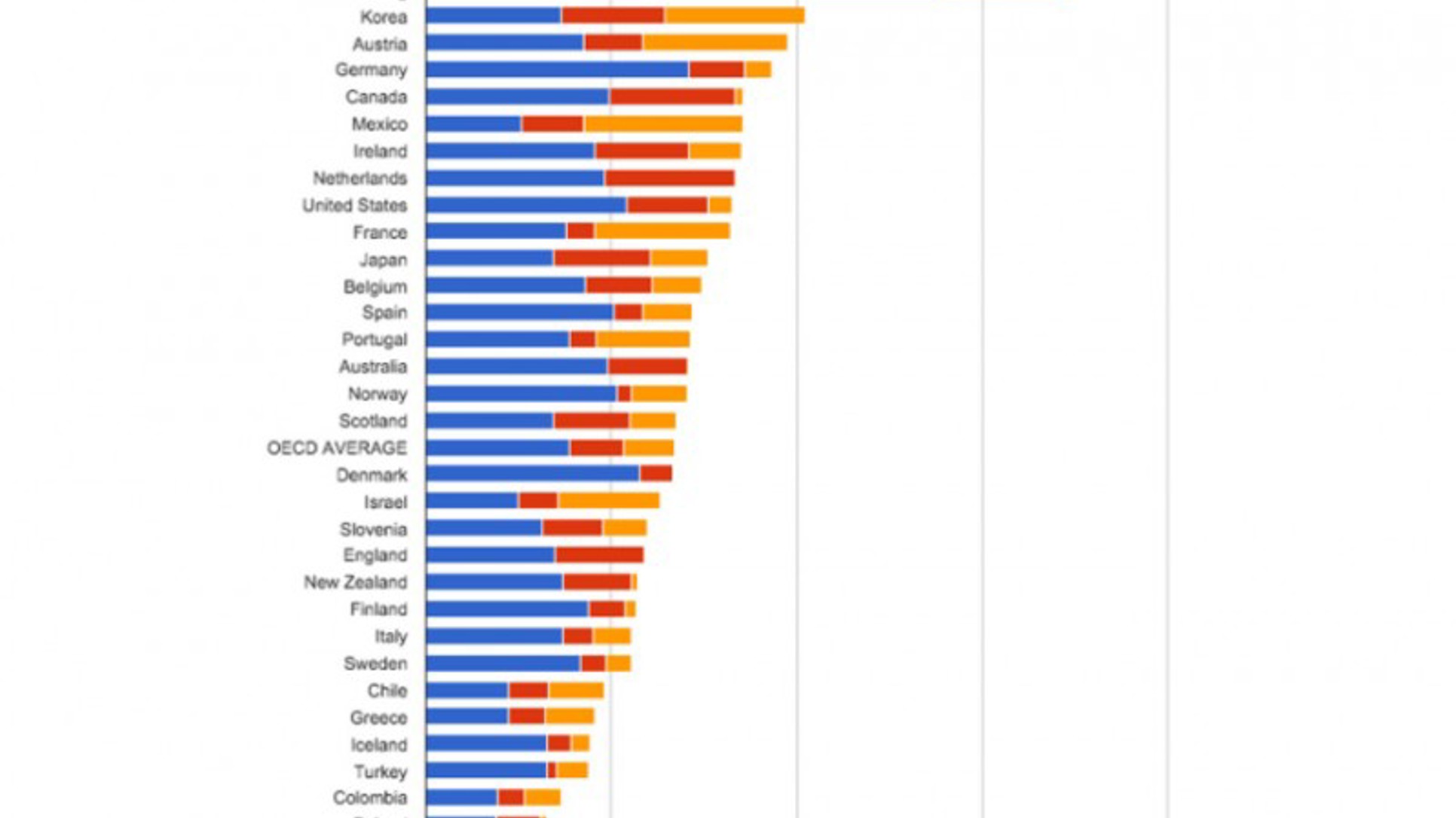

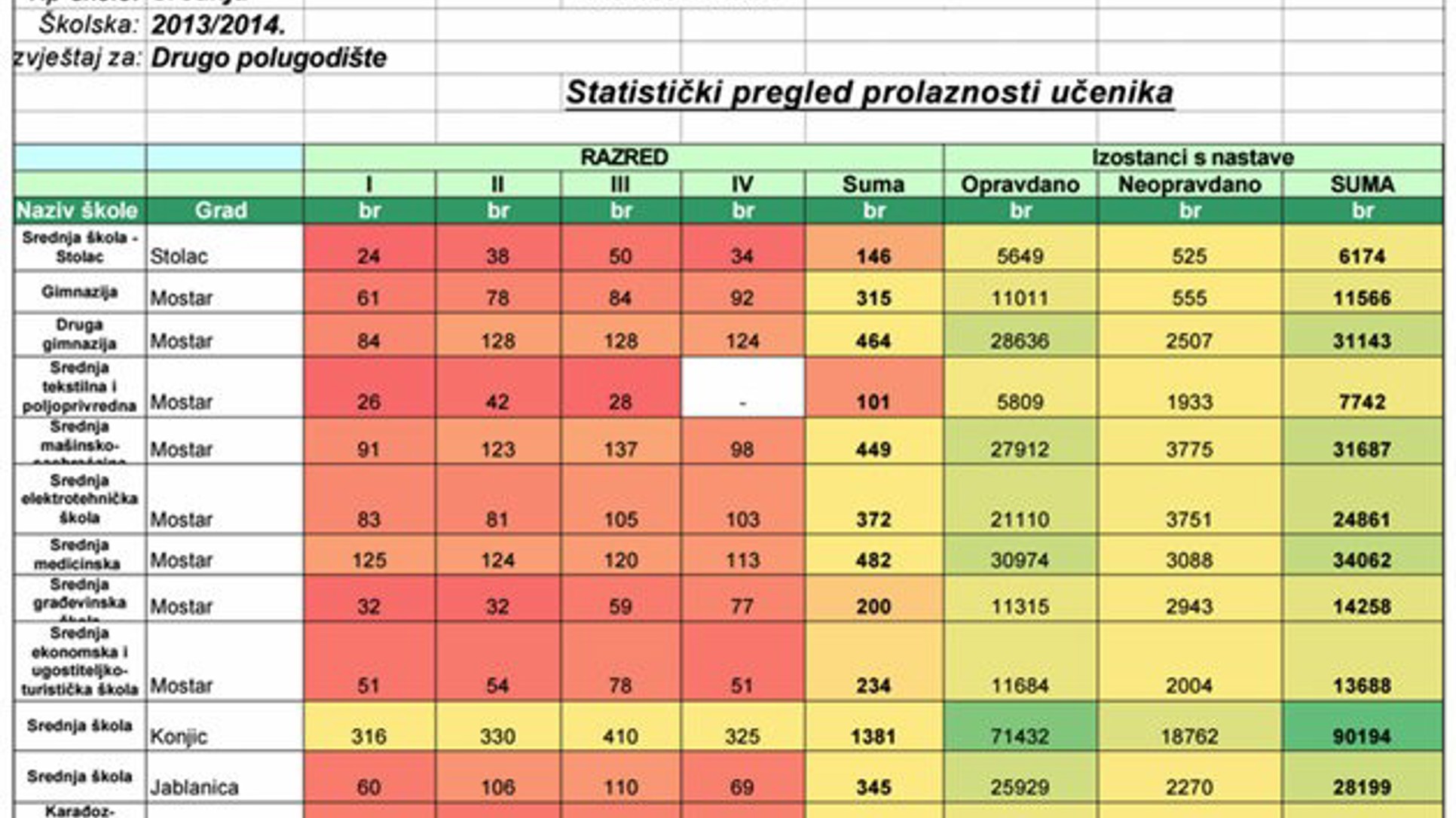

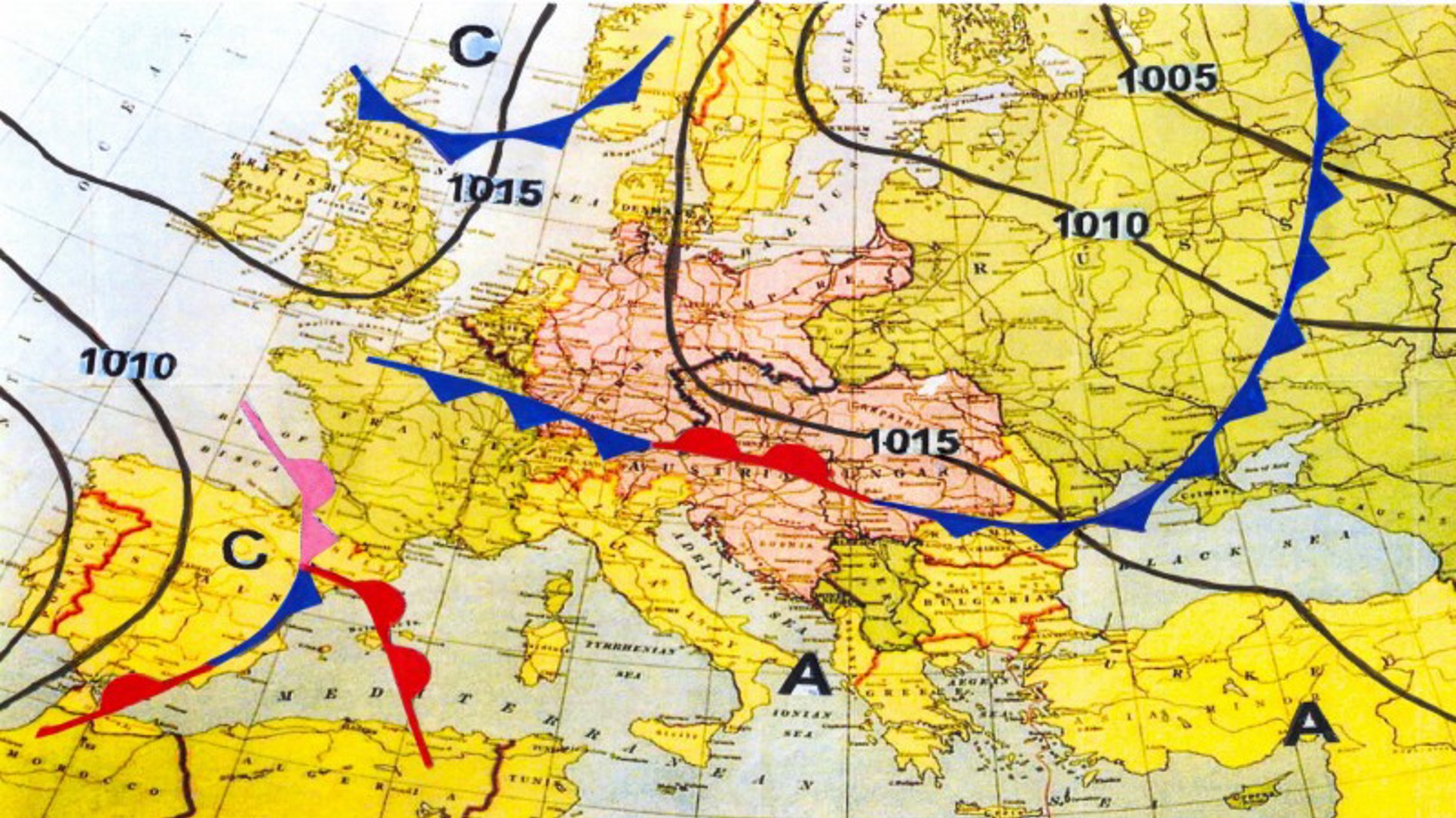

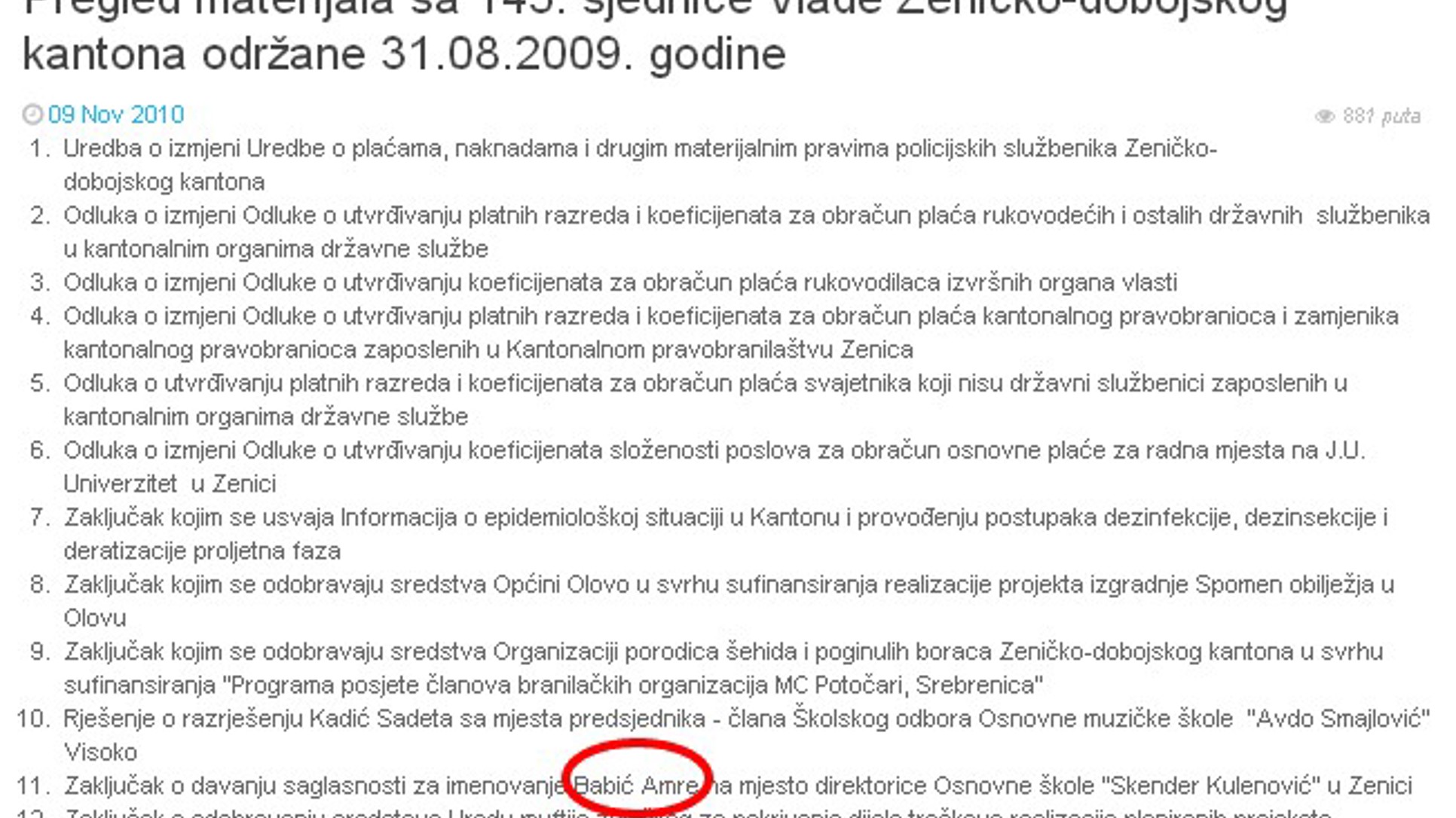

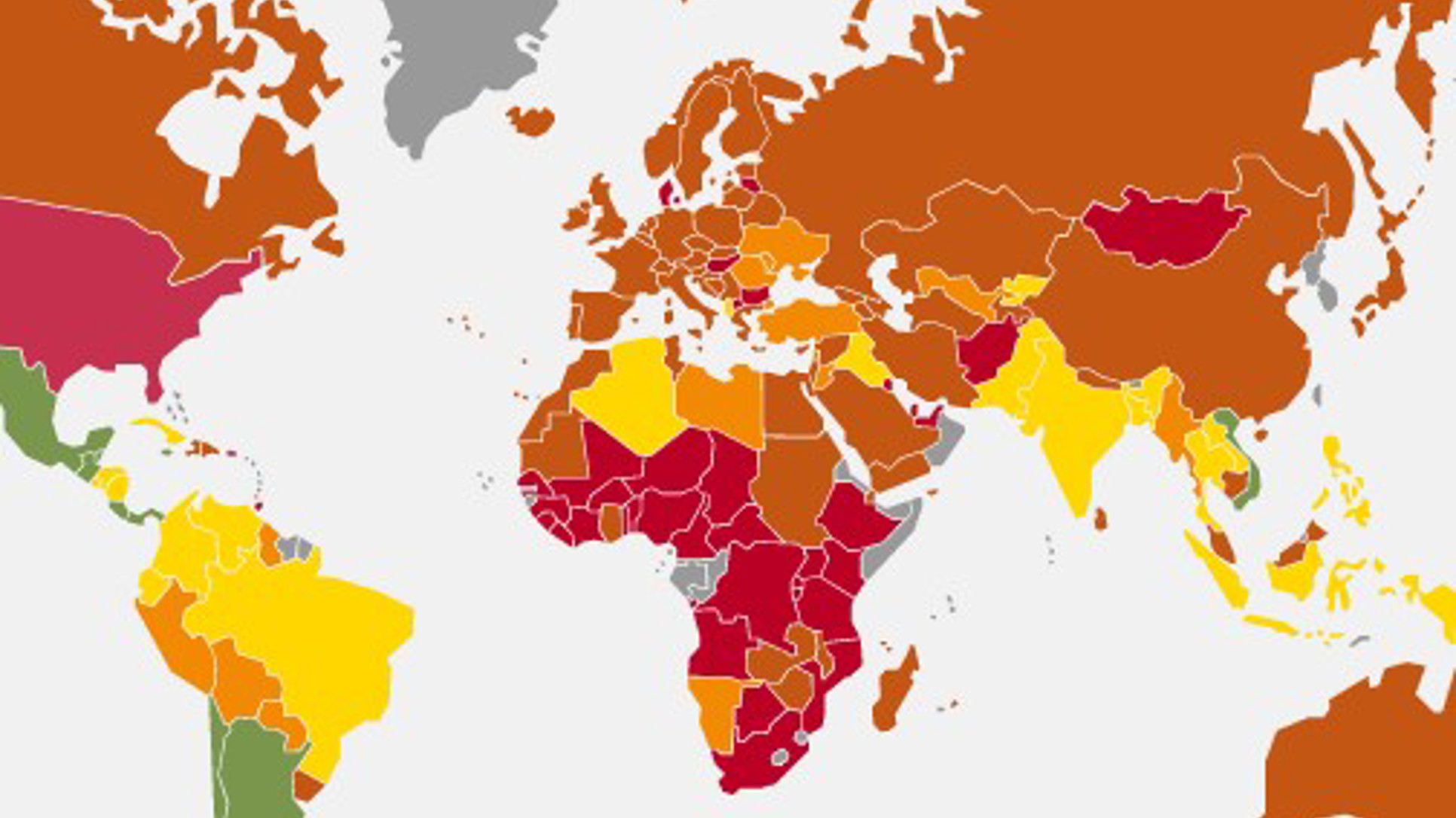

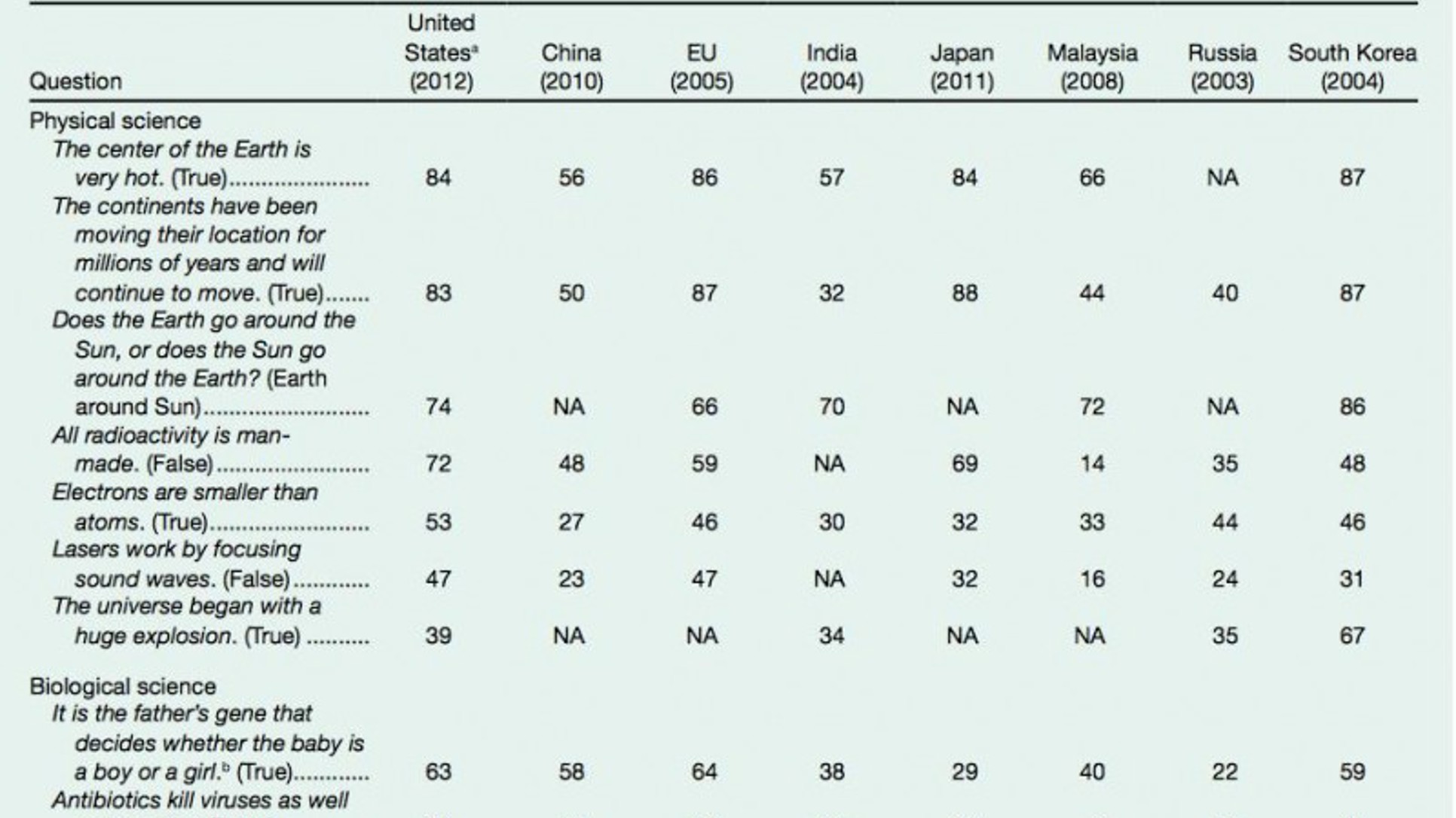

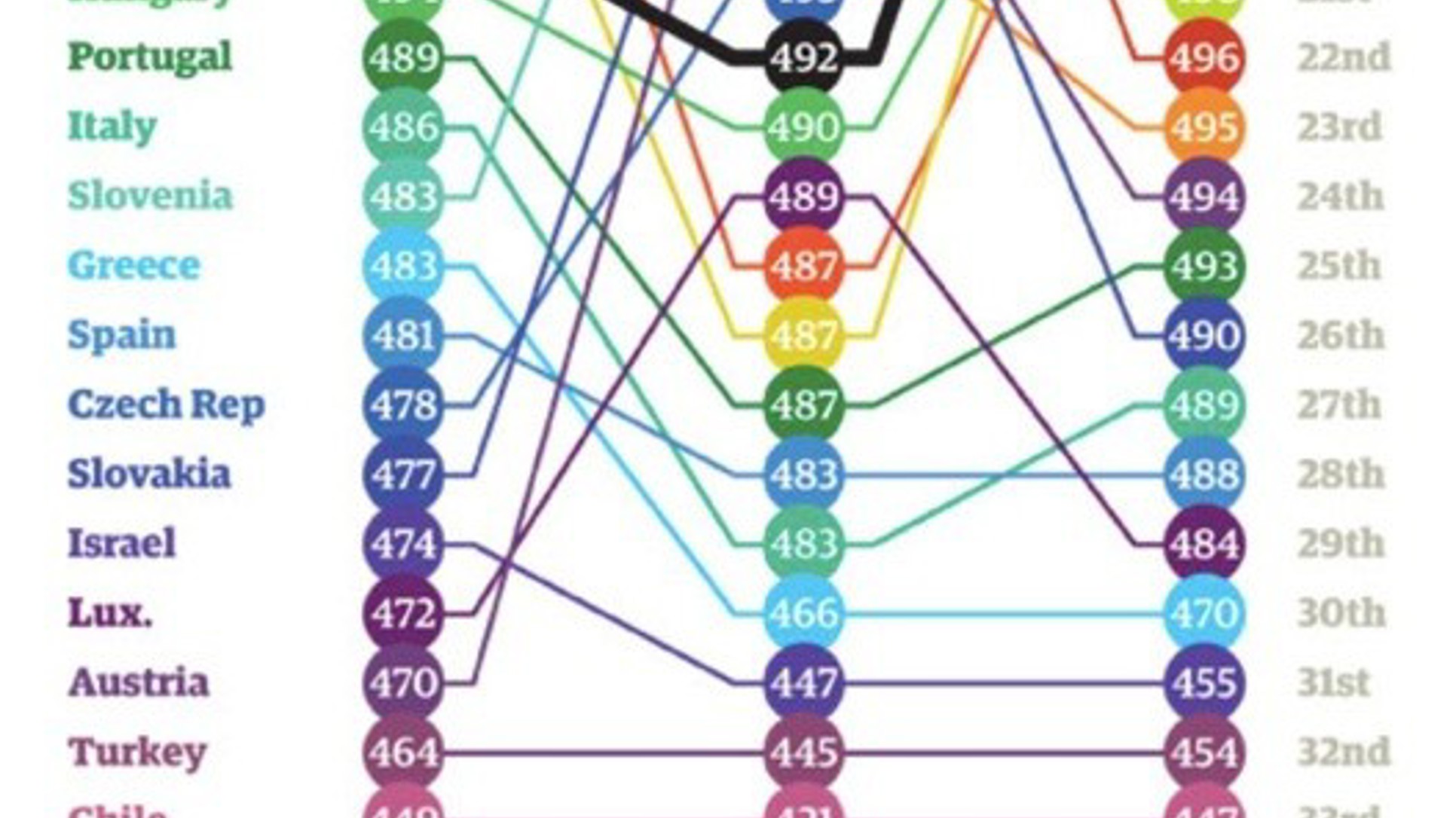

How are these approximately 50 percent of children who do not distinguish between fact and opinion distributed around the world?

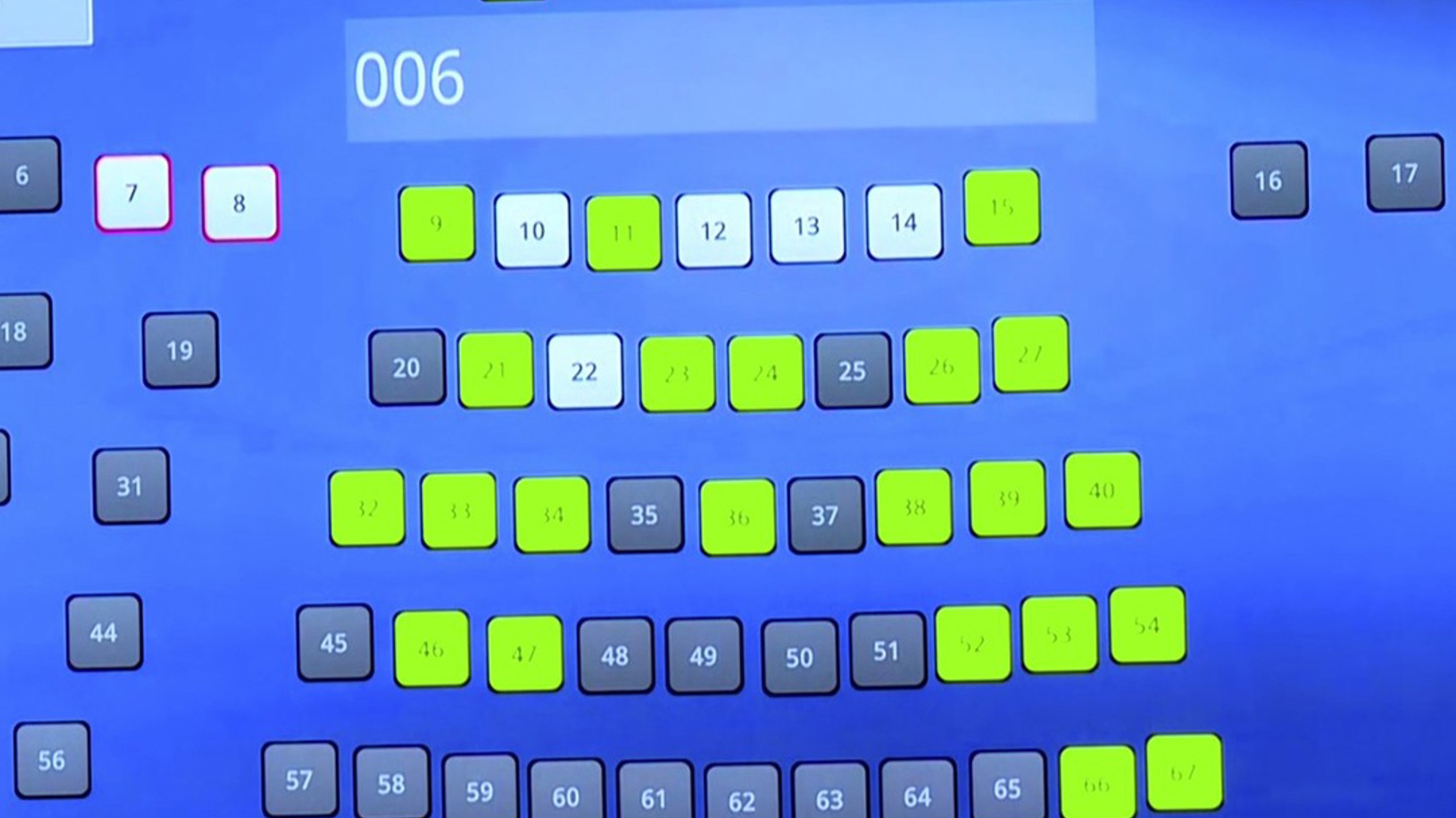

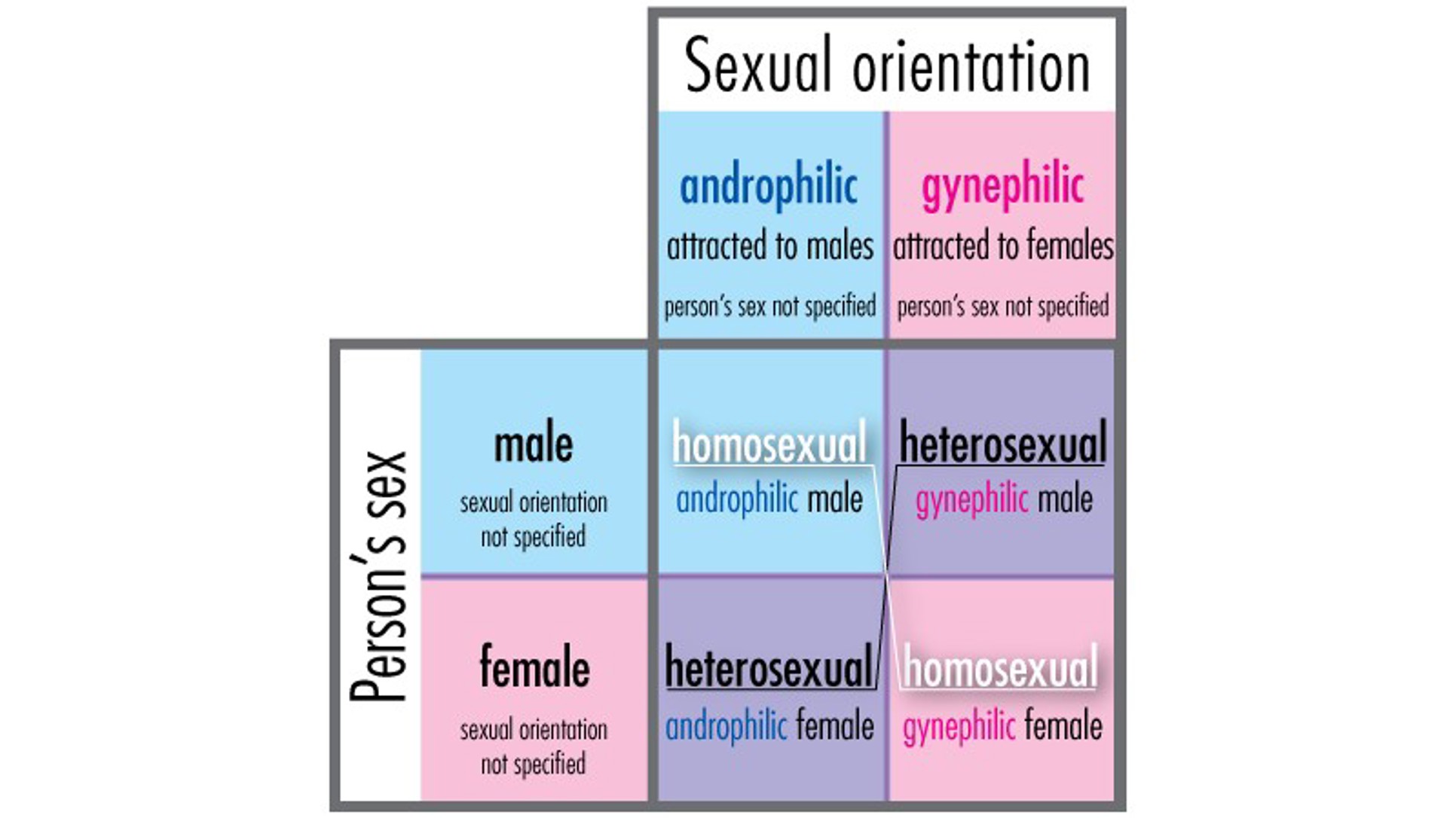

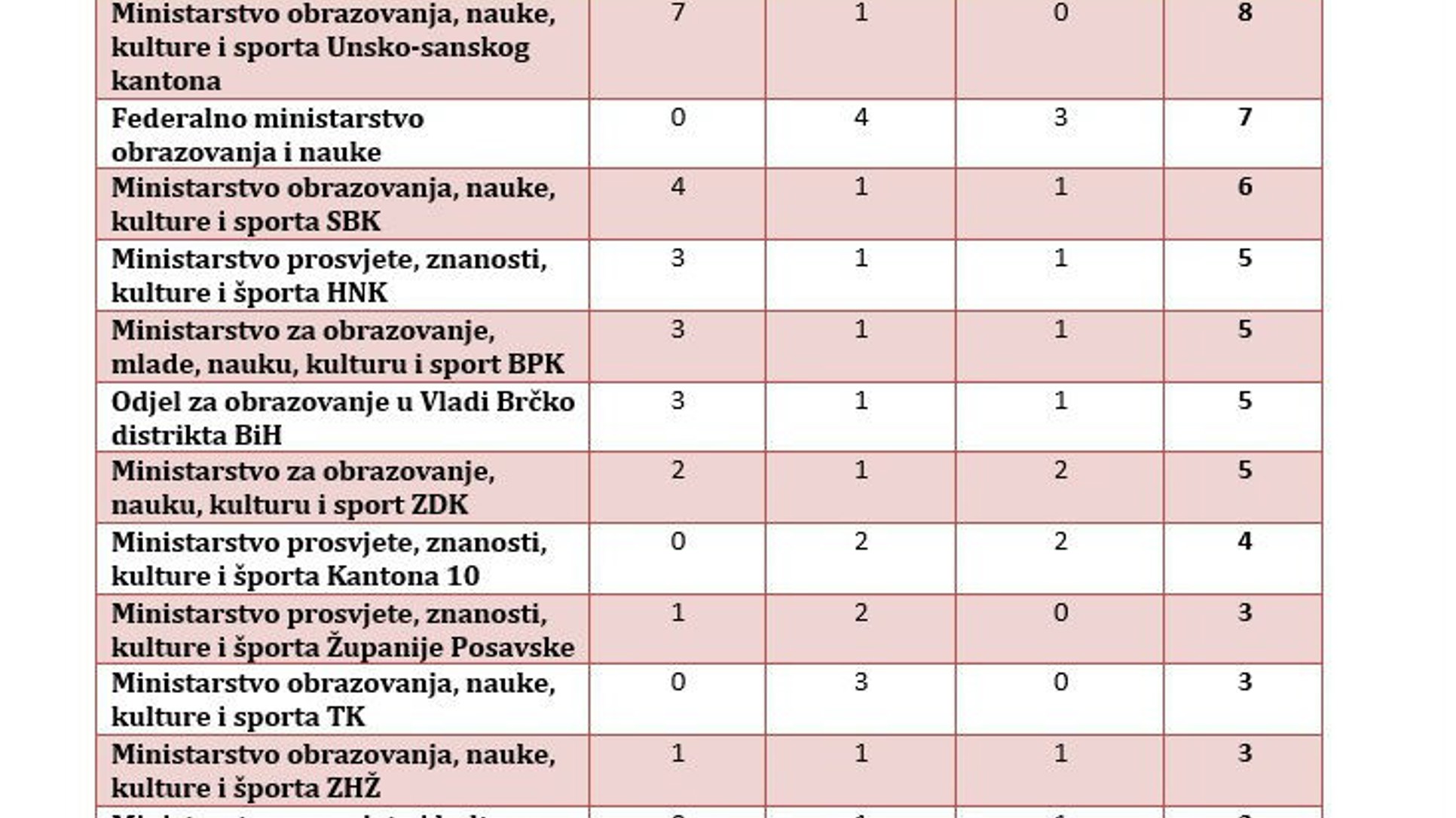

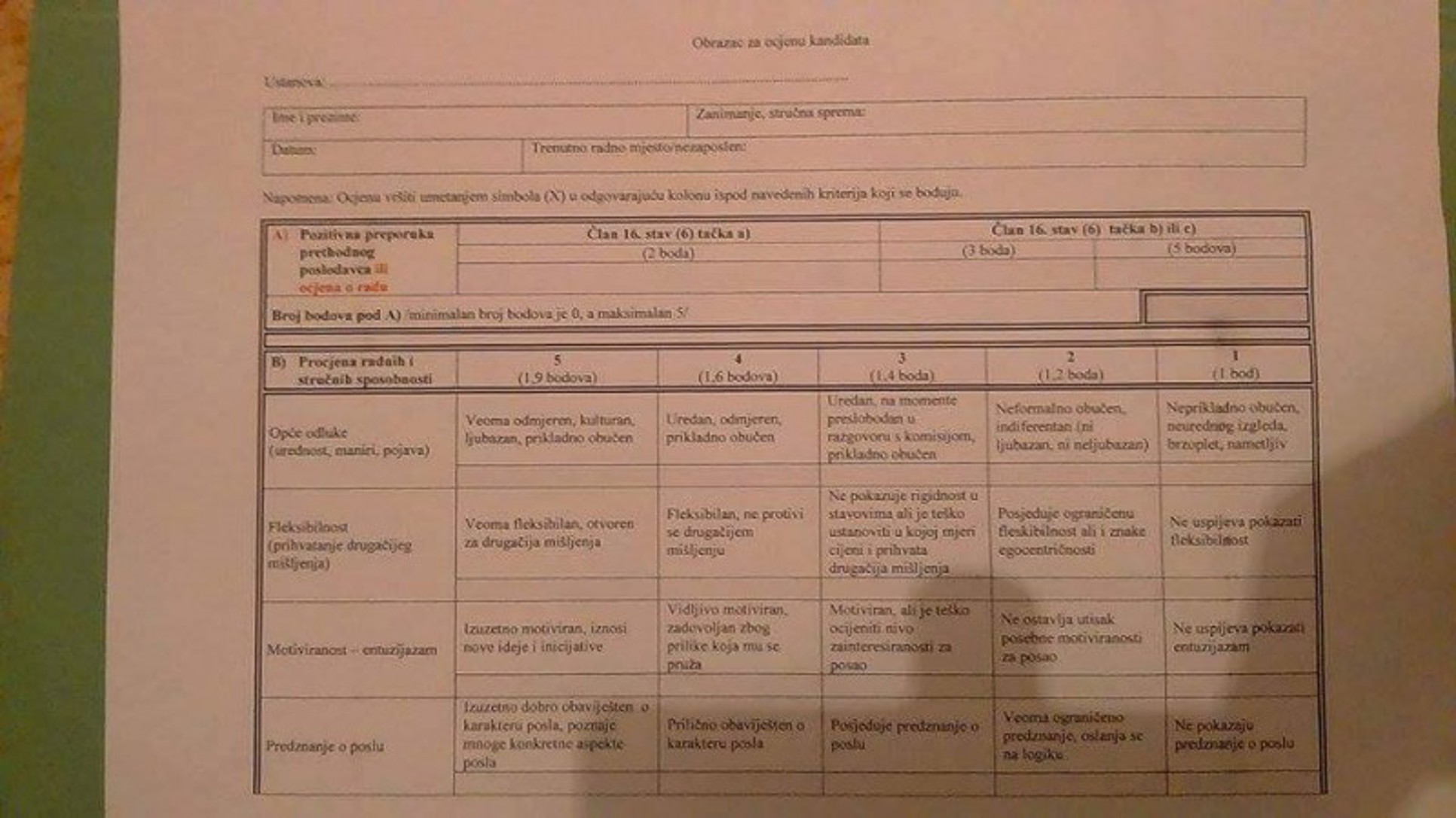

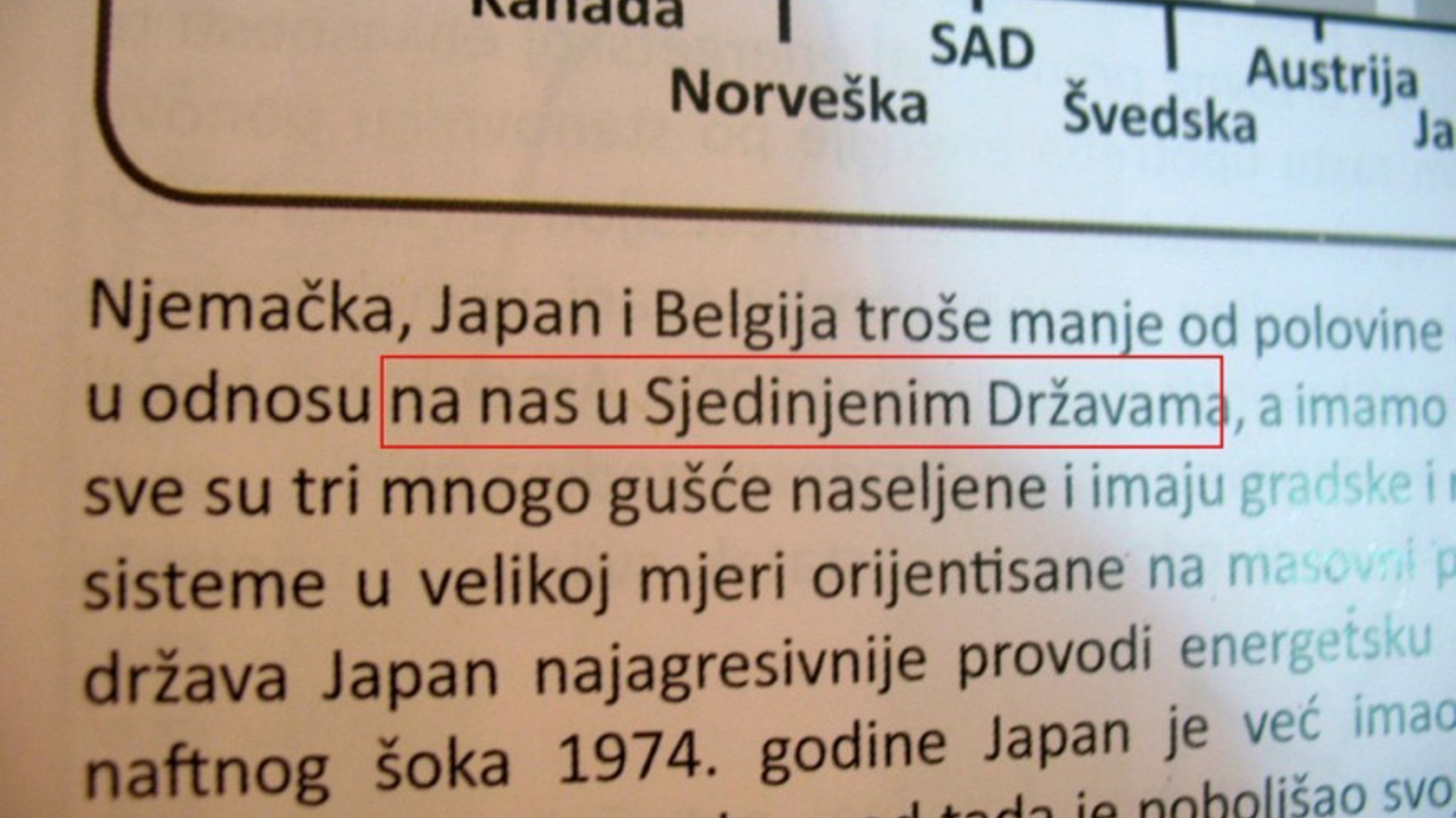

There are large variations across OECD countries, from about 25% of students in Korea who responded correctly to this specific item in the PISA 2018 reading assessment, up to 70% in the United States. See the figure below, extracted from a PISA in Focus issue that investigated this question in more depth: “Are 15-year-olds prepared to deal with fake news and misinformation?”

Are there any recommendations to overcome this situation?

PISA 2018 showed that education systems with a higher proportion of students who were taught how to detect biased information in school and who have digital access at home were more likely to distinguish fact from opinion in the PISA reading assessment, even after accounting for country per capita GDP. The first correlation suggests that schools can foster proficient readers in a digital world by closing these gaps and teaching students basic digital literacy, so that they develop autonomous and advanced reading skills that include the ability to navigate ambiguity, and triangulate and validate viewpoints. The second correlation reminds us that digital literacy skills are a form of digital skills. Thus, ensuring good access to, and proper use of, digital technology in education can be key to the development of students digital literacy skills.

To support this change in teaching, learning and assessment practices across the whole education system, governments can use public policy as a tool to cultivate the digital literacy of all education stakeholders, as is described further below.

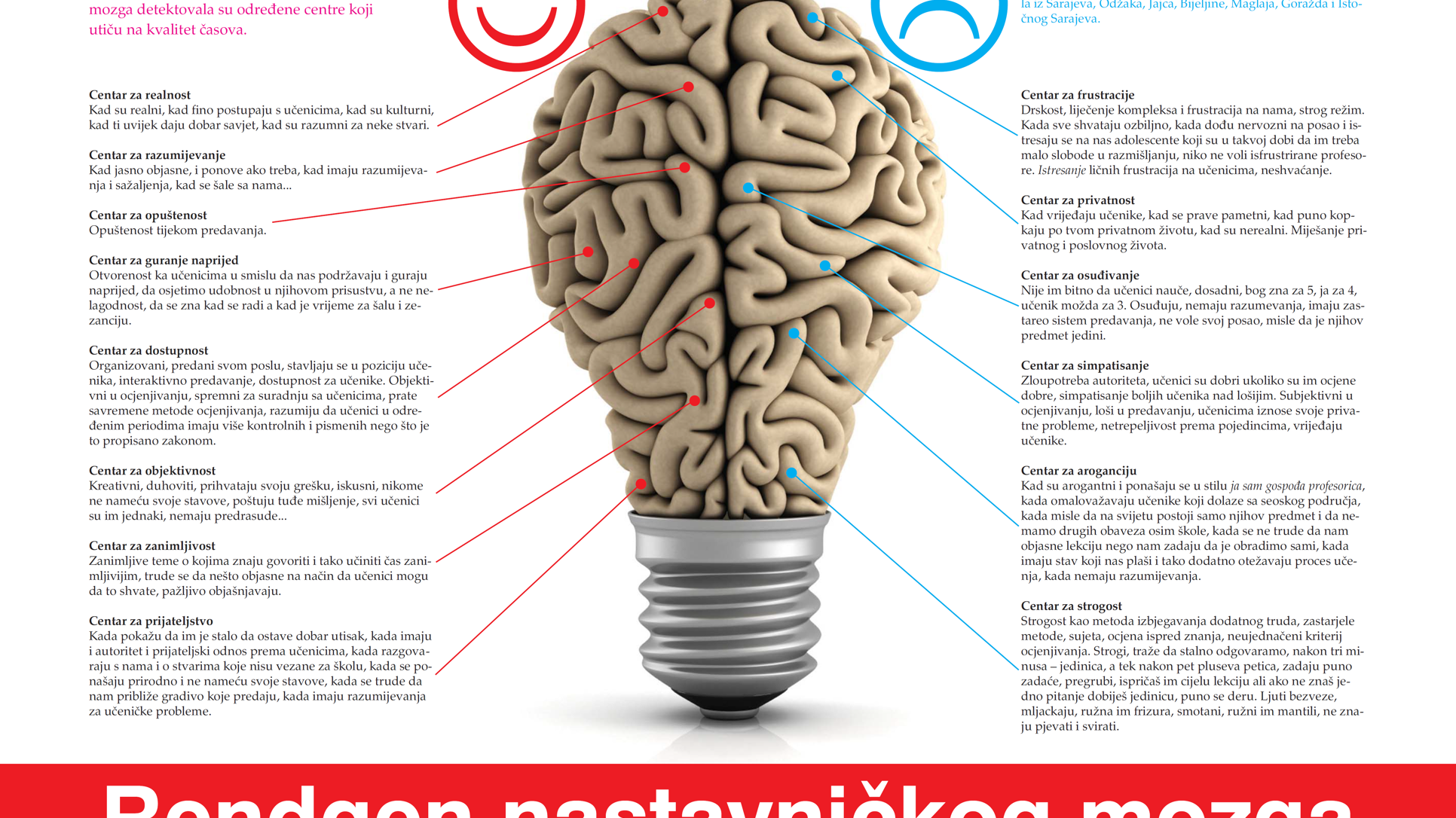

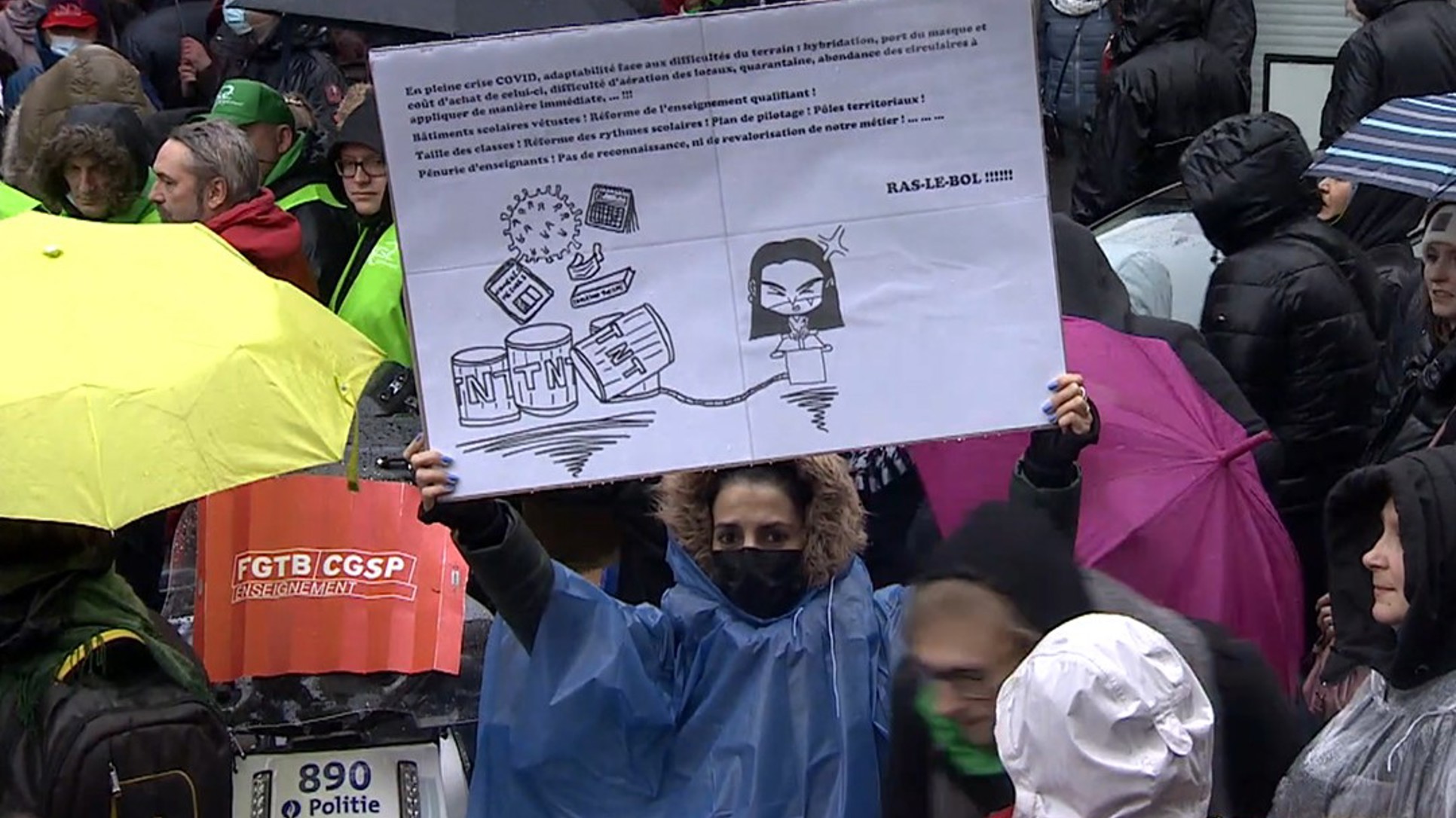

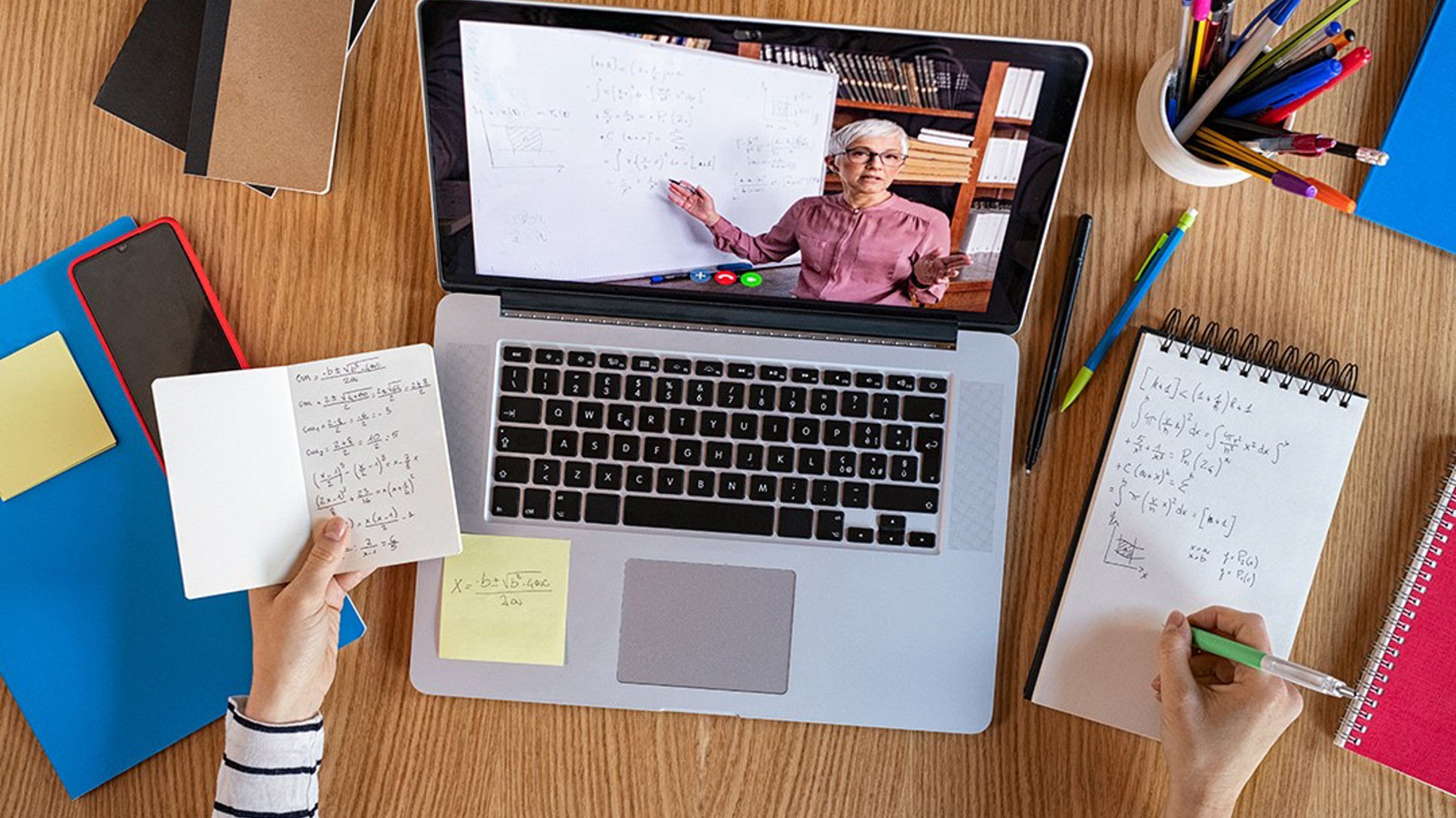

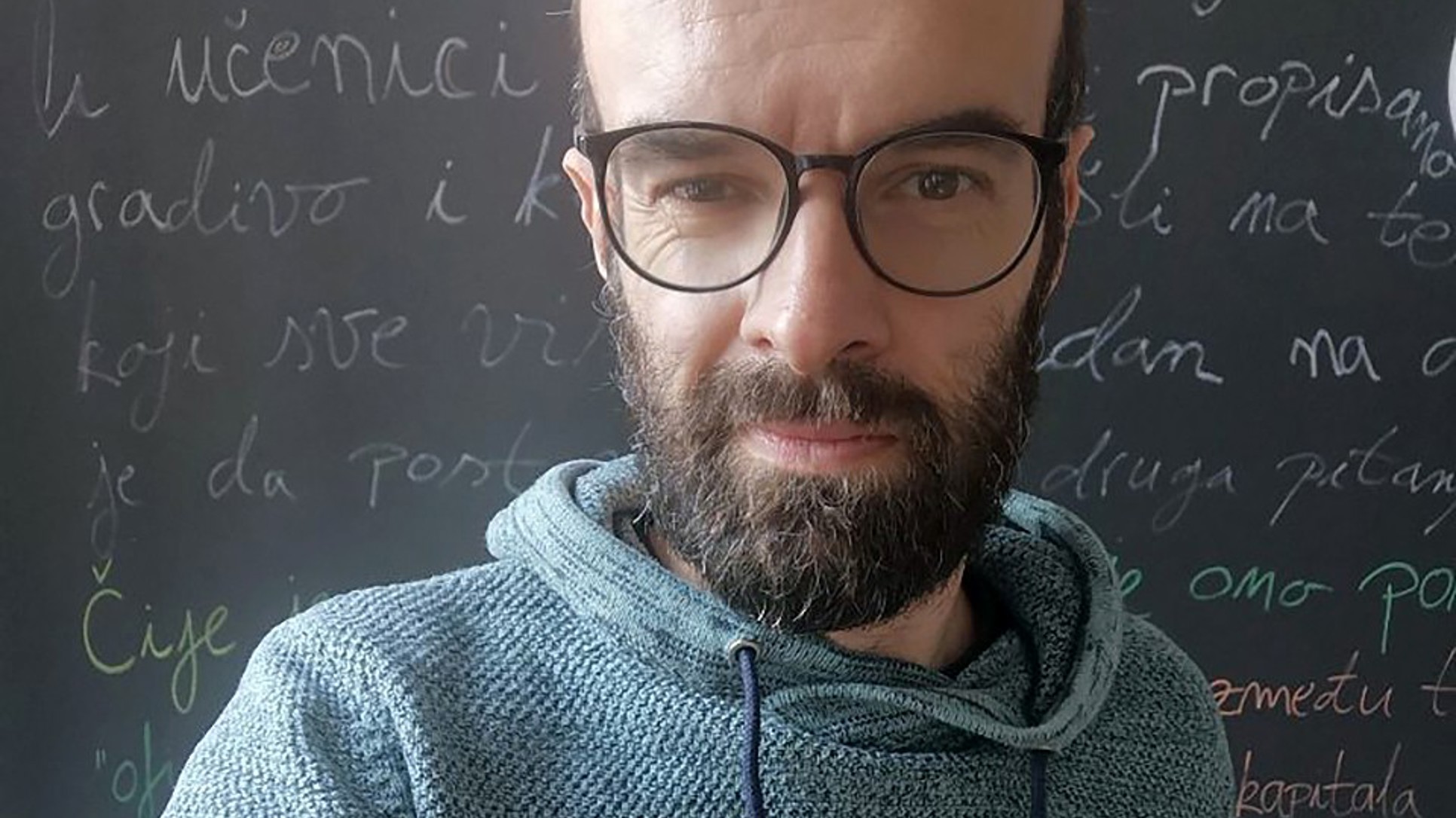

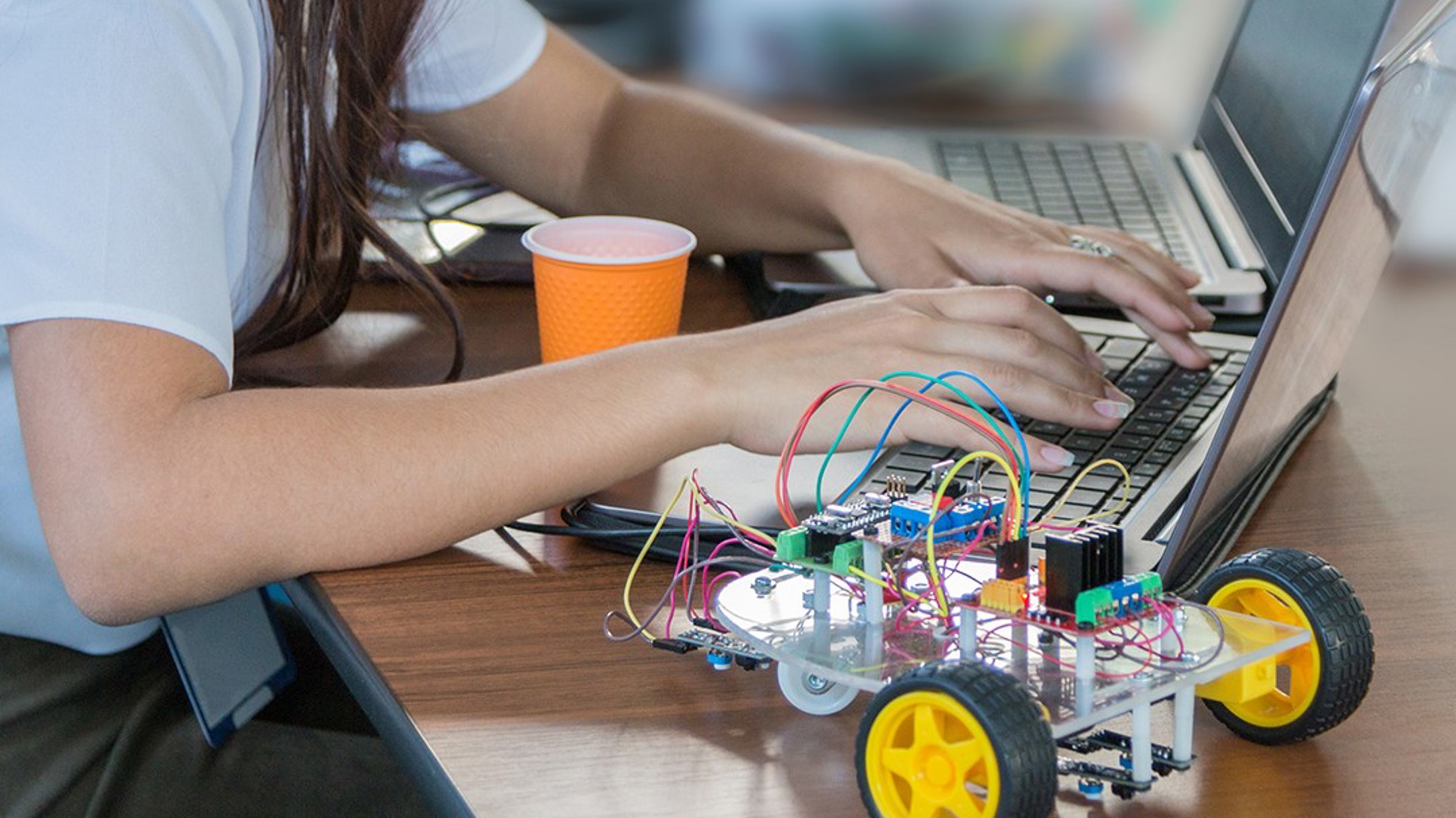

How much does teacher education have to do with it, is it being worked on, in what direction should we act and do we have a unique solution for it because somewhere only the best students become teachers, and somewhere teaching is a refuge for not very good students?

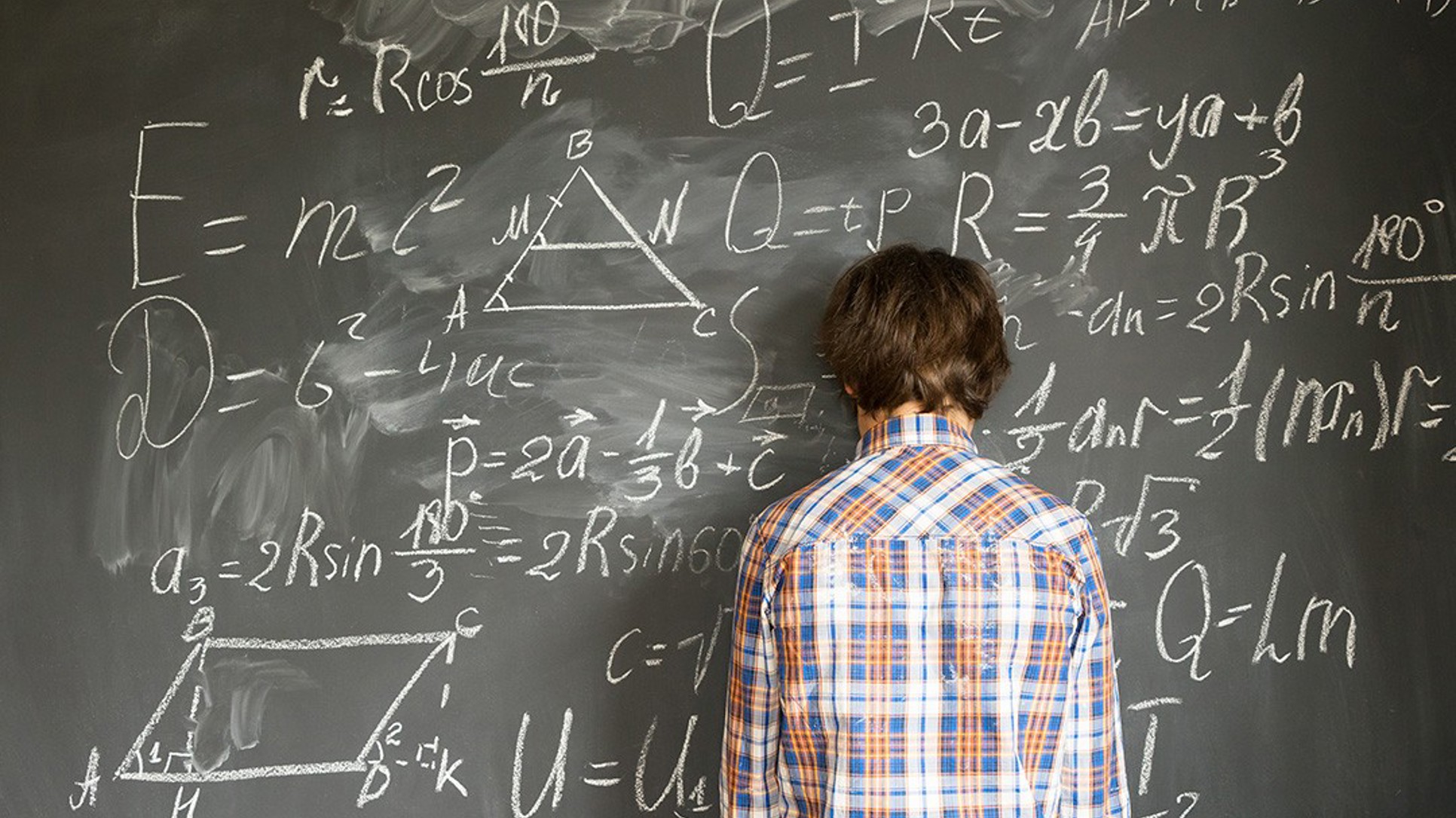

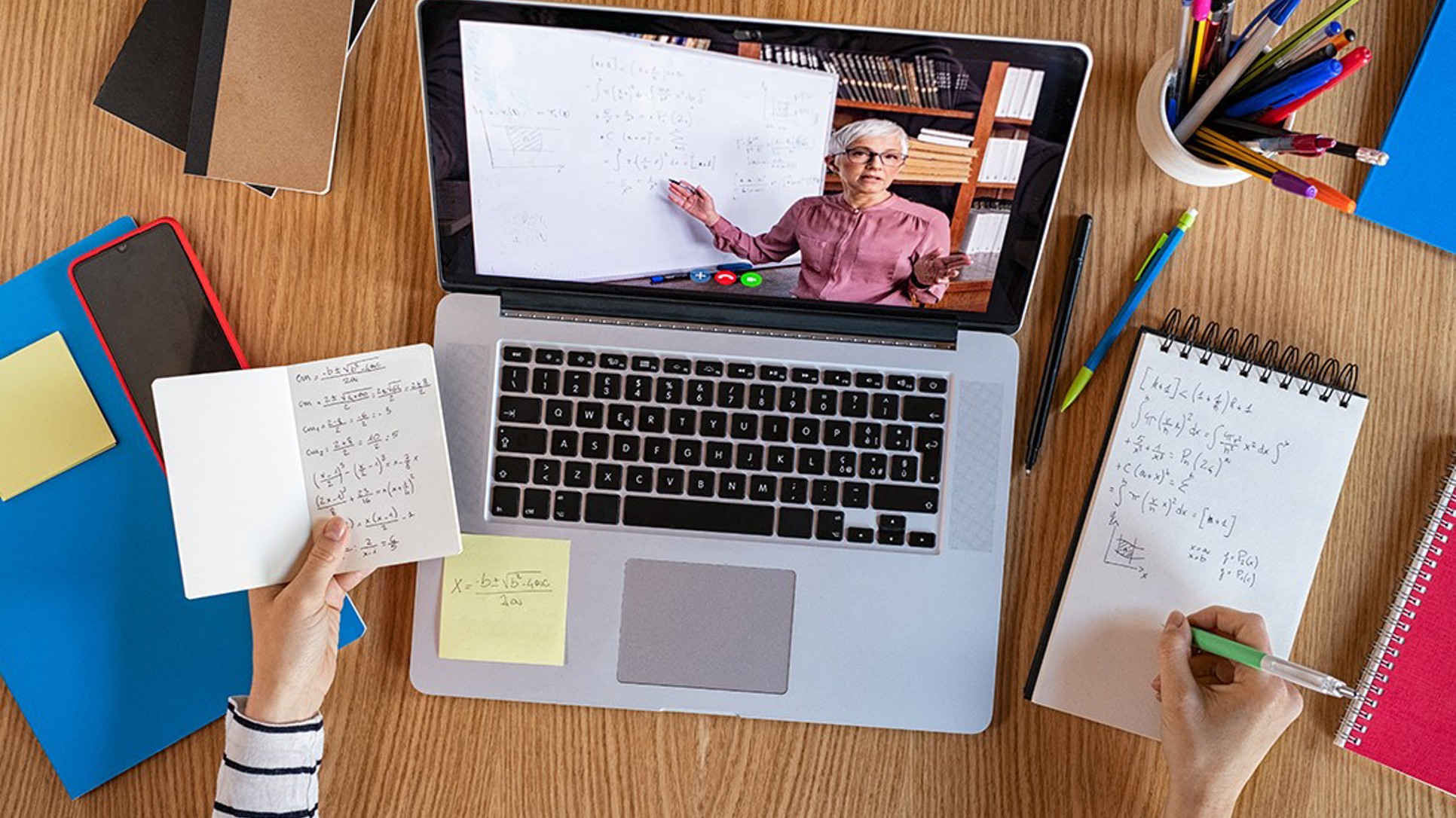

Teacher education is one key to address the problem of students’ digital literacy. Digital literacy skills are also digital skills, and that’s perhaps where the first policy efforts are most needed. The OECD TALIS 2018 study showed that, on average across the OECD, only 56% of lower secondary teachers had received a formal pre-service training in the use of ICT for teaching; and 61% of them reported that they take part in professional development in ICT skills. Proportions considerably vary across countries, and sometimes even within country depending on school characteristics (urban or rural, private or public, high or low concentration of disadvantaged students).

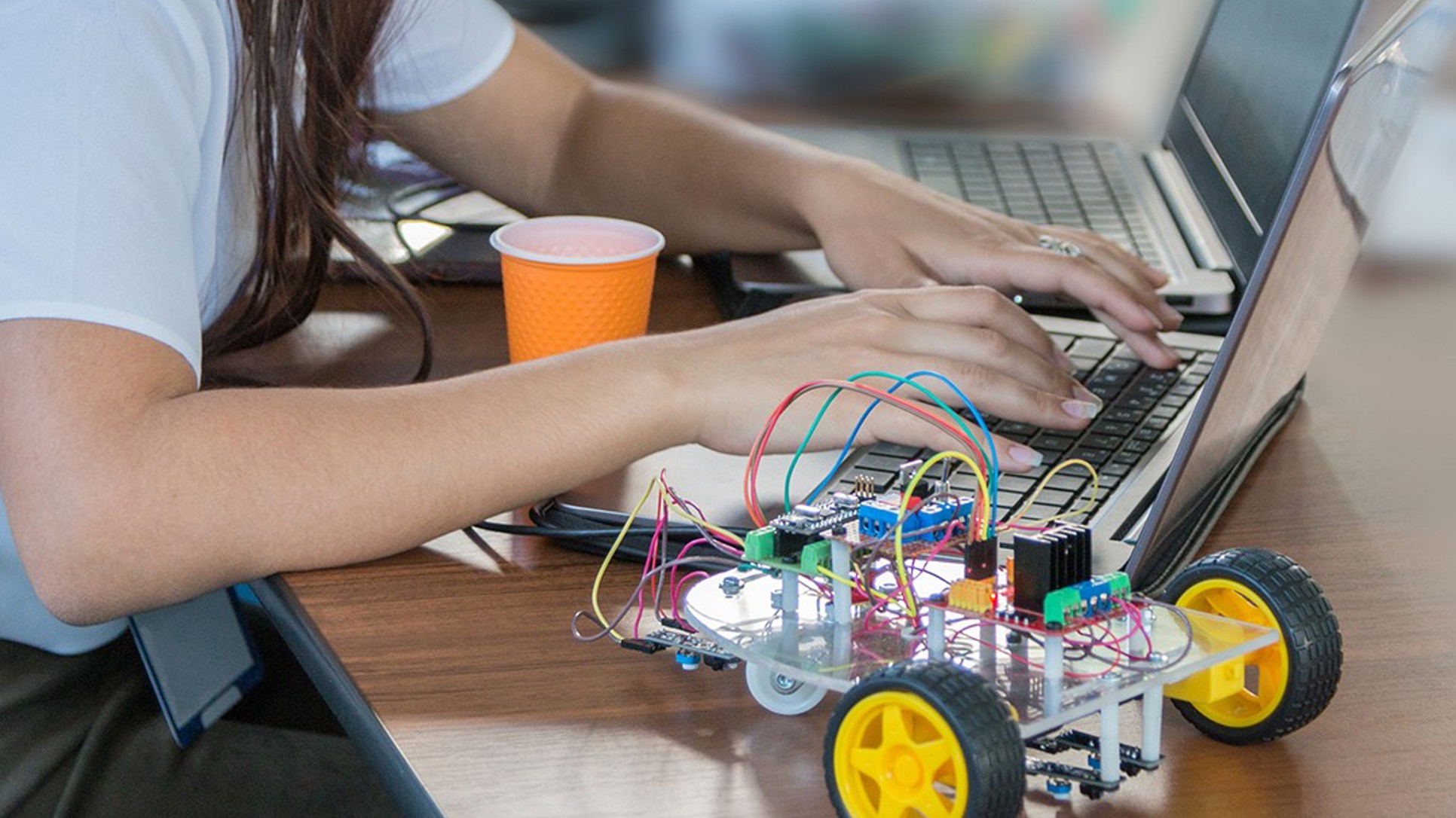

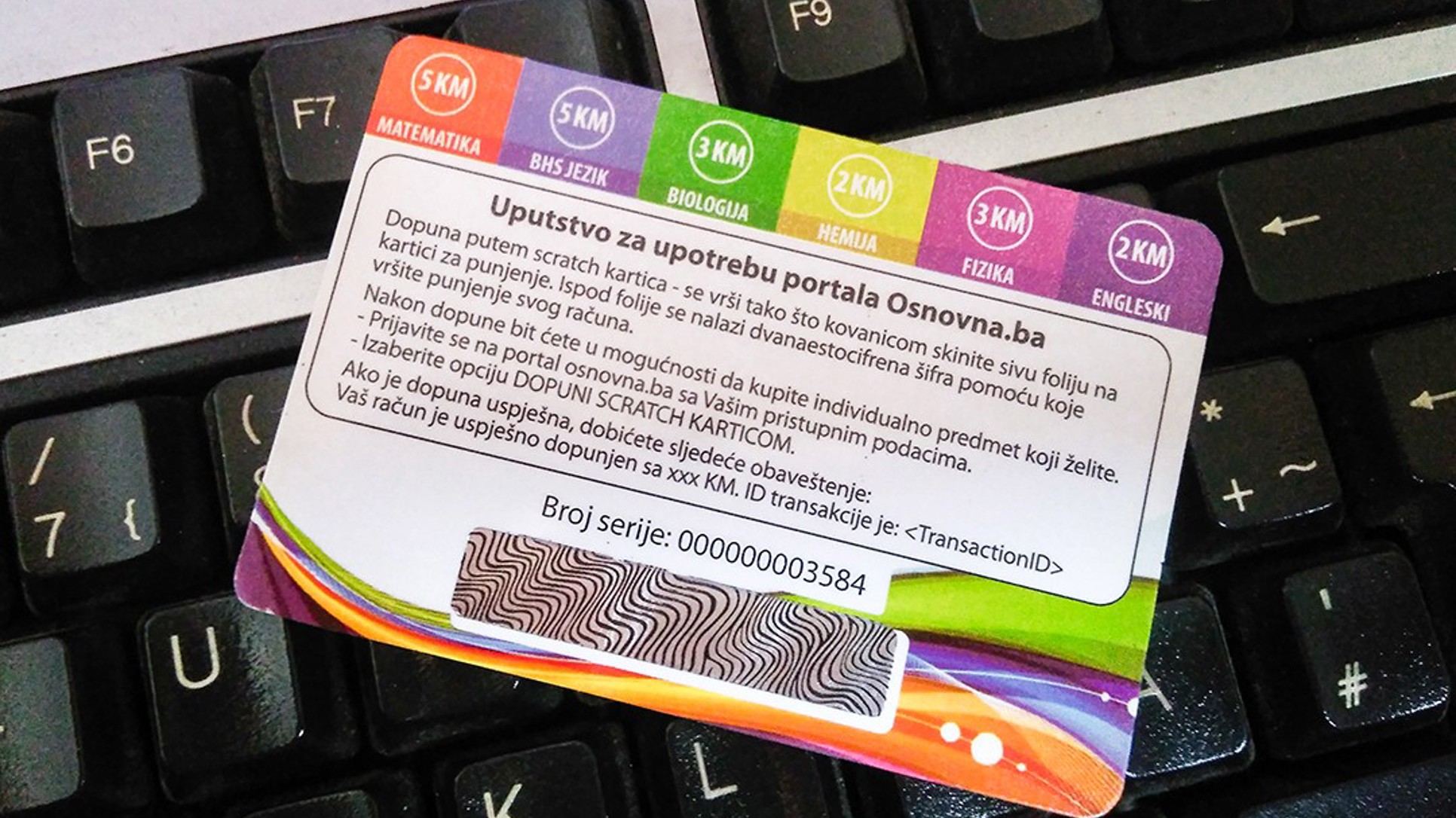

With the right training, teachers could improve their own and their students’ digital literacy; provided that students’ curricula are adjusted accordingly. In the work that we conduct for the next OECD Digital Education Outlook 2023, we try to see how countries’ public policy can cultivate the digital literacy of all education stakeholders and what we observe is more often the other way round. Few examples arise of policy efforts that explicitly aim at integrating the use of digital technology in teachers’ pre-service or in-service training (partly because teacher education is not always a publicly managed responsibility). More often, requirements to use digital technology in the classroom are first integrated to the national curriculum of students, which de facto leads teachers to acquire certain competences around ICT, media literacy or programming, for instance.

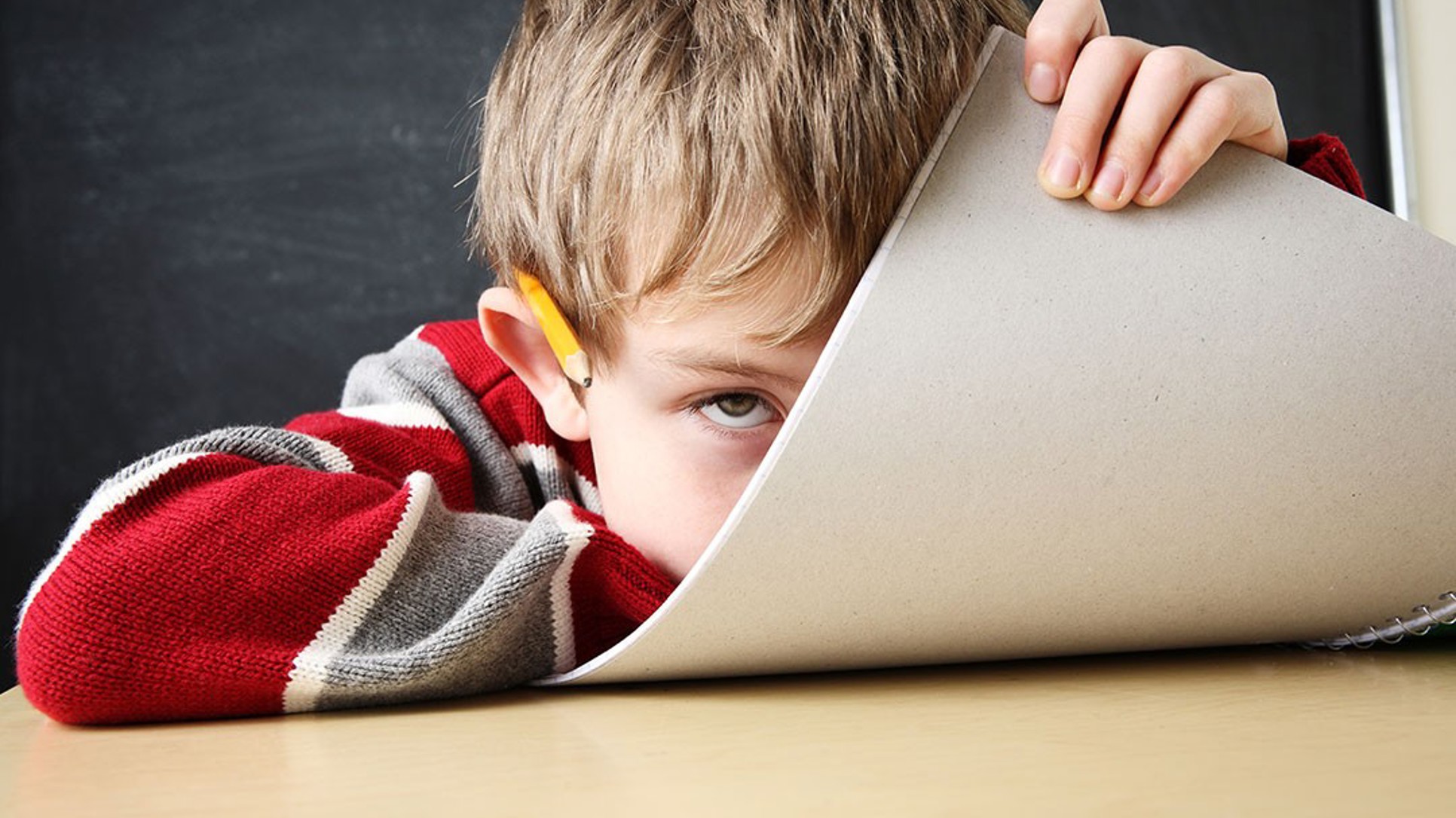

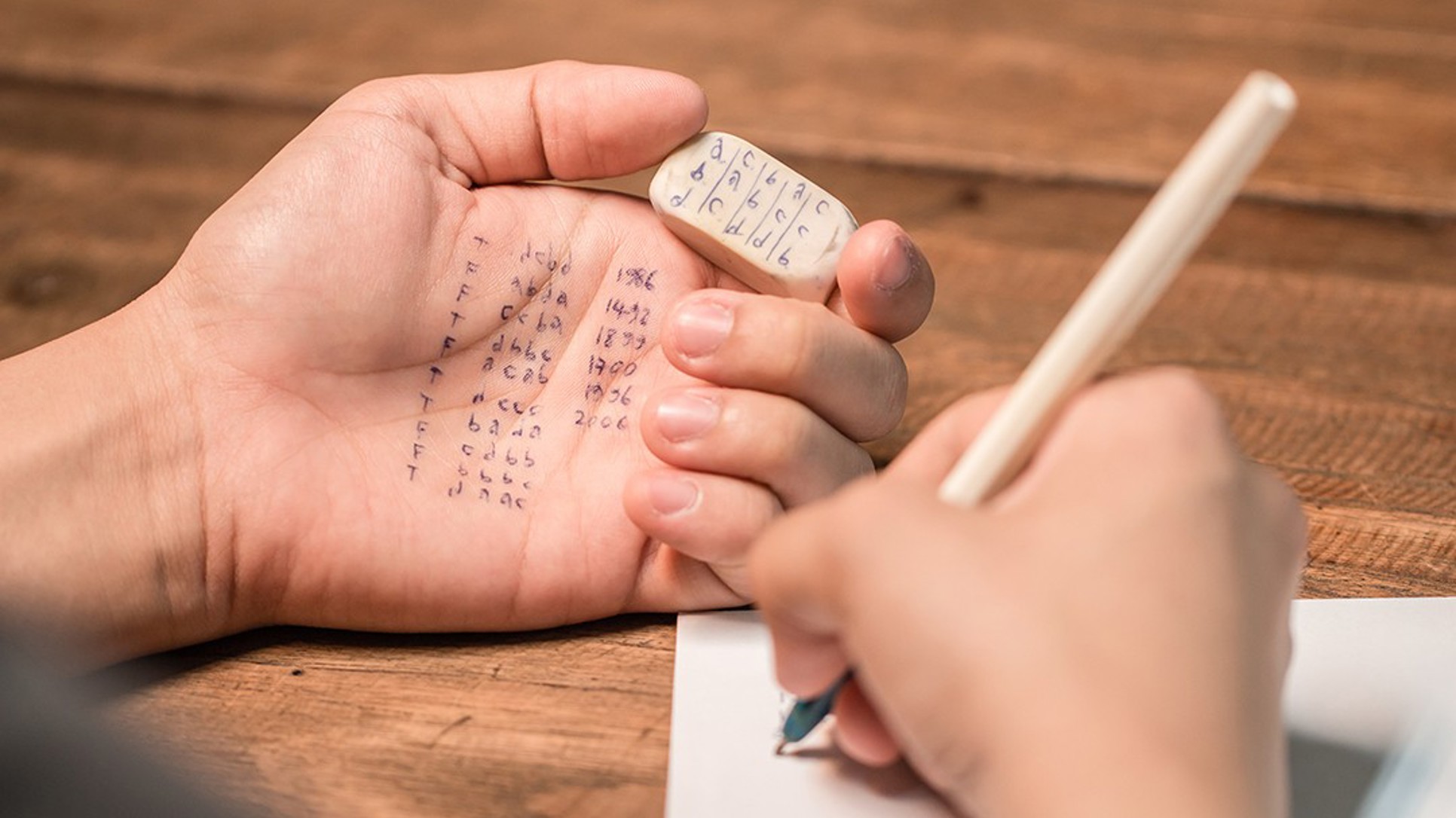

However, in this state of play students’ digital literacy is too heterogeneously fostered. In PISA 2018, fifteen-year-old students reported that they had limited opportunities to learn digital literacy skills during their entire school experience. If, on average across the OECD, 76% students reported they had been taught how to understand the consequences of making information publicly available online on social media, (way) fewer were taught how to decide whether to trust the information from the Internet, how to compare different web pages and decide what information if more relevant for their schoolwork, how to use keywords when using a search engine, how to detect whether the information is subjective of biased, or how to detect phishing or spam emails. And those averages hide considerable variations across countries.

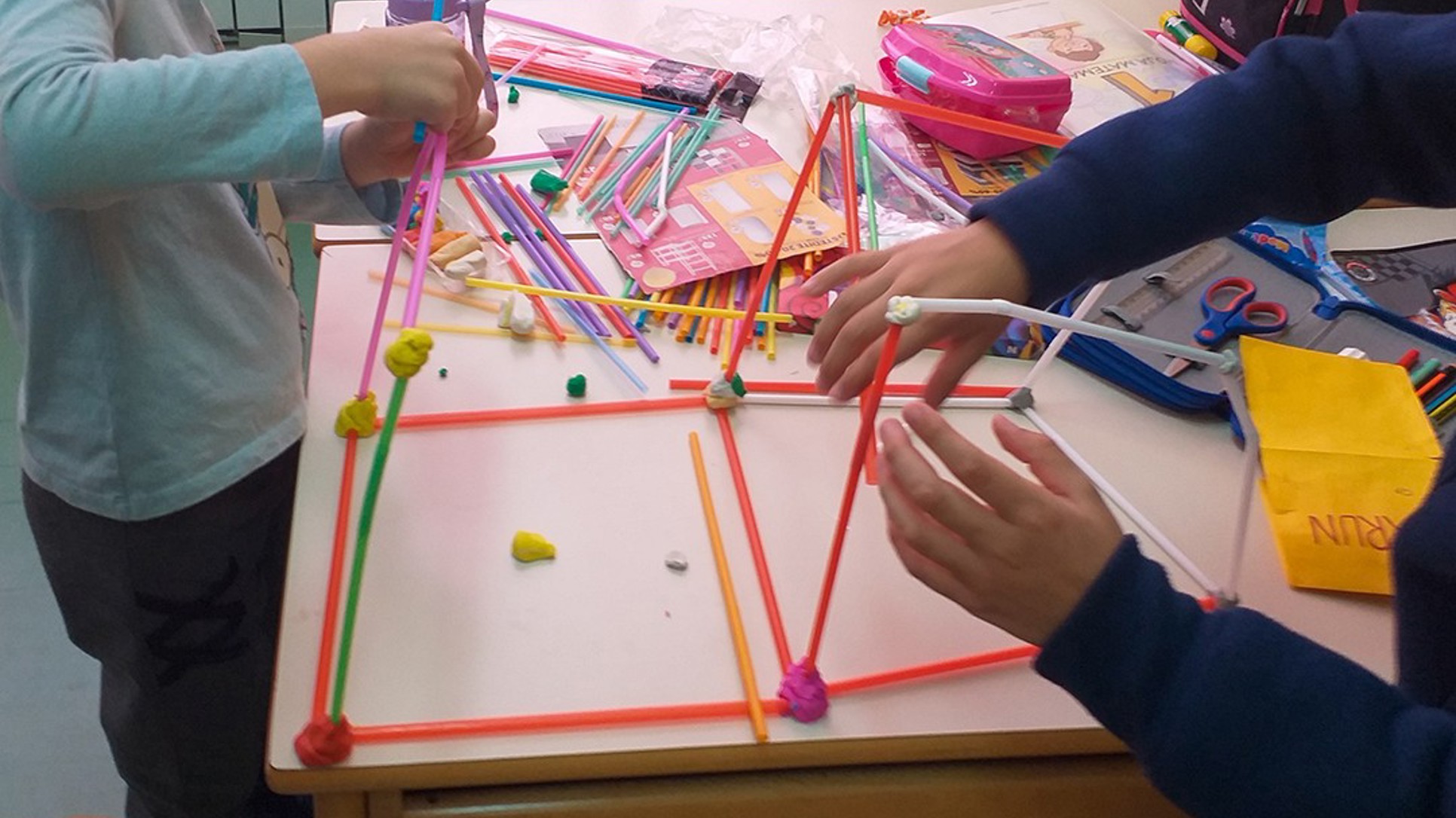

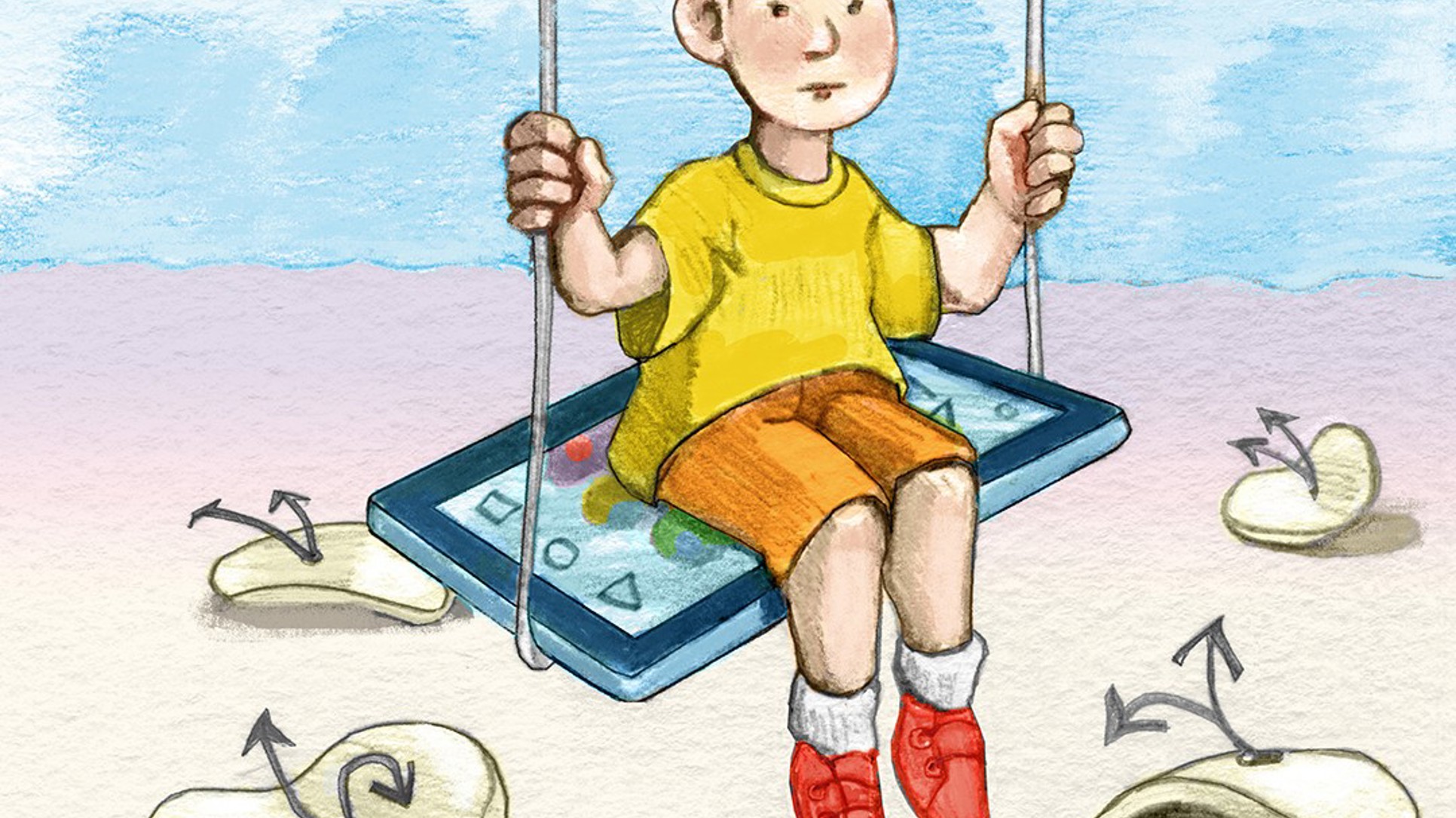

We are also talking about an individualized approach to teaching - what should it look like in a class?

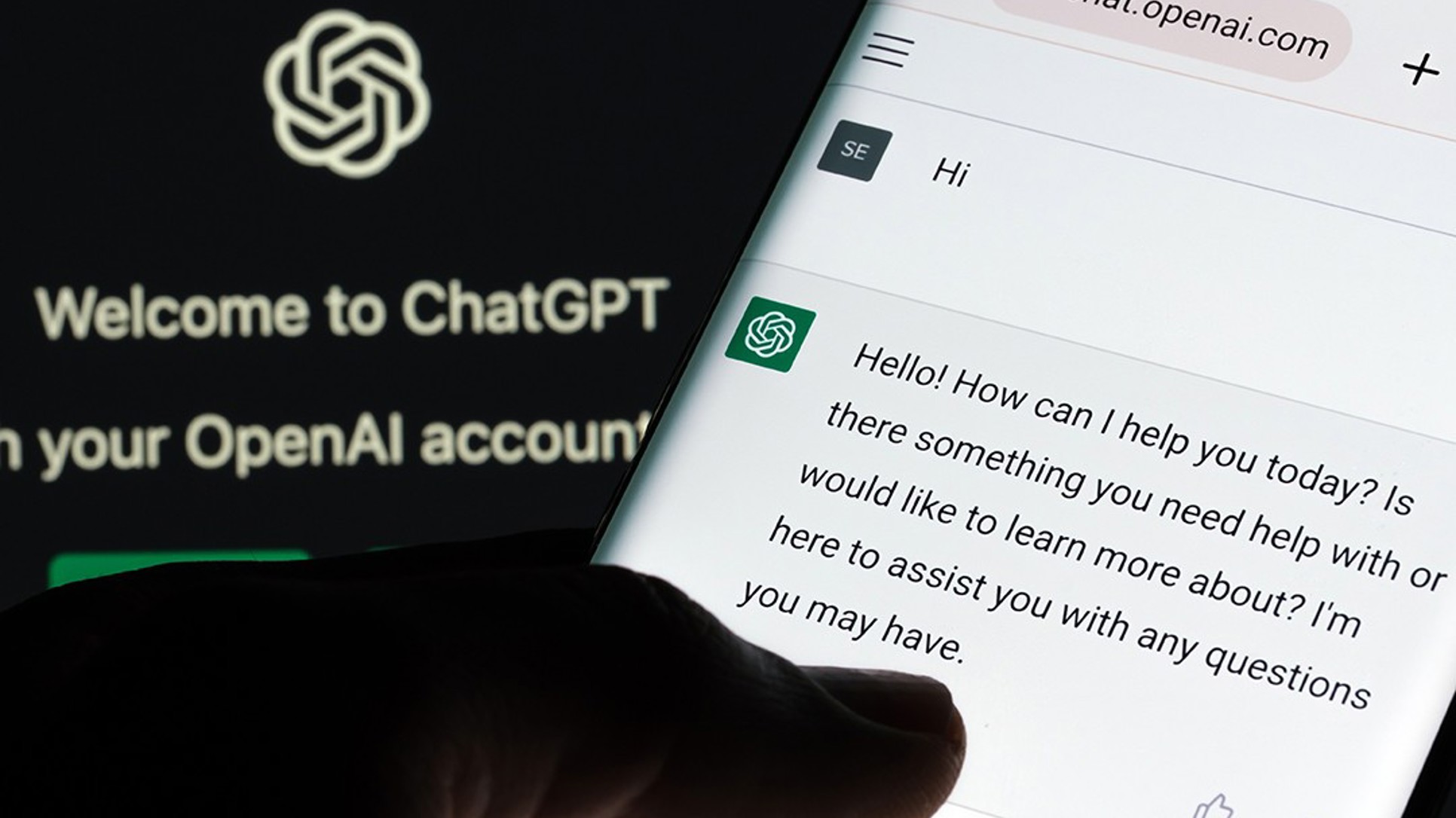

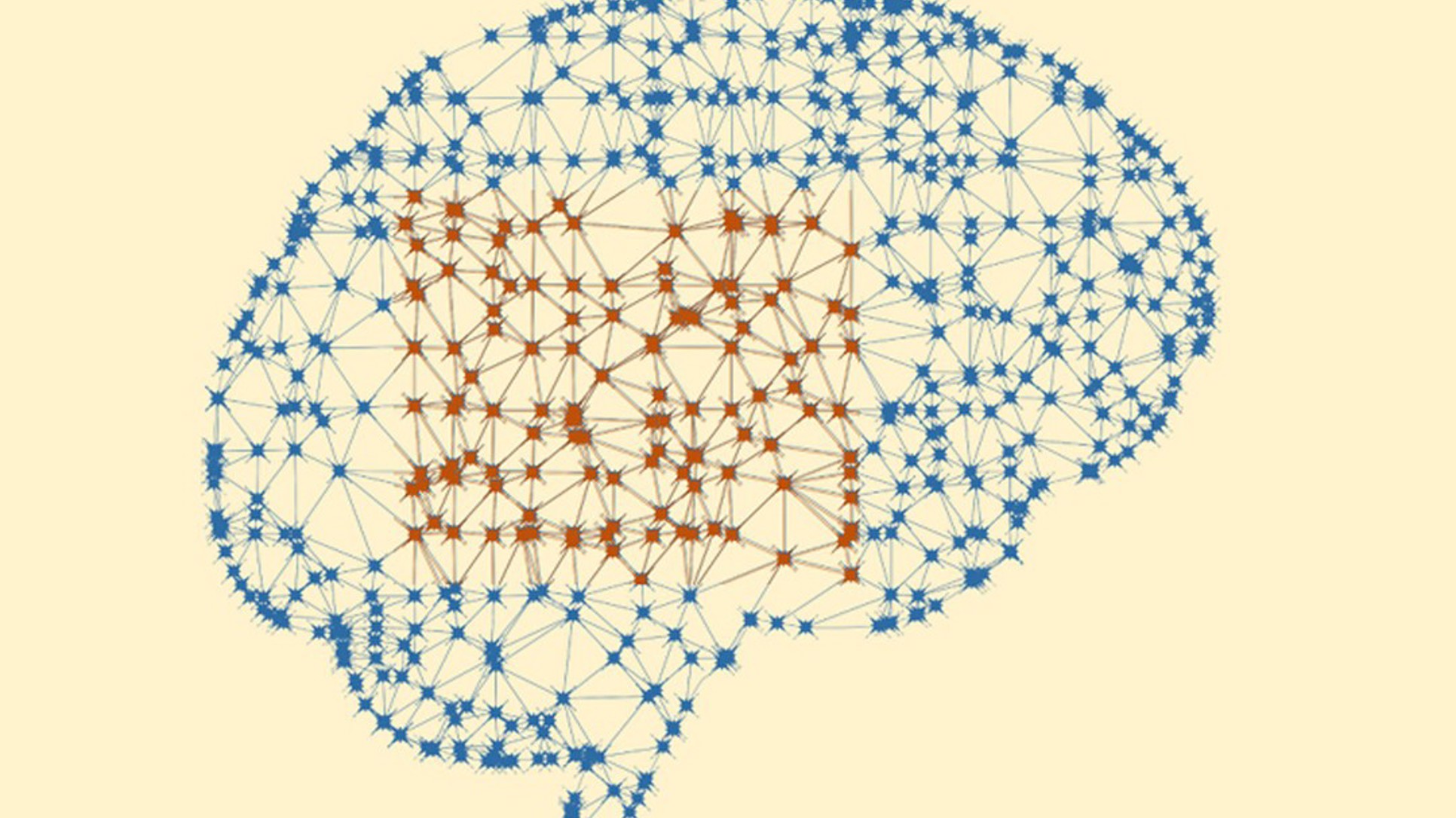

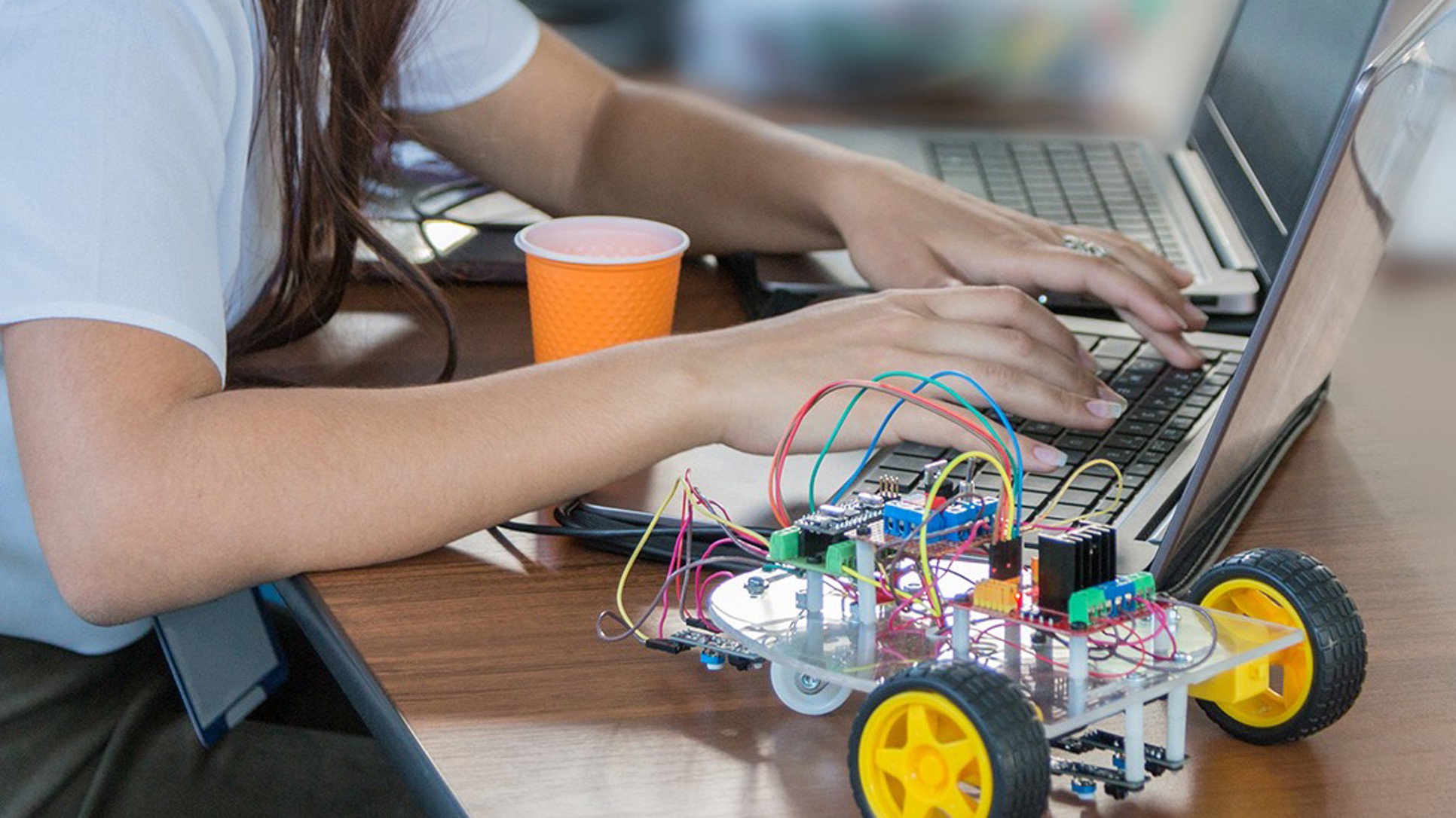

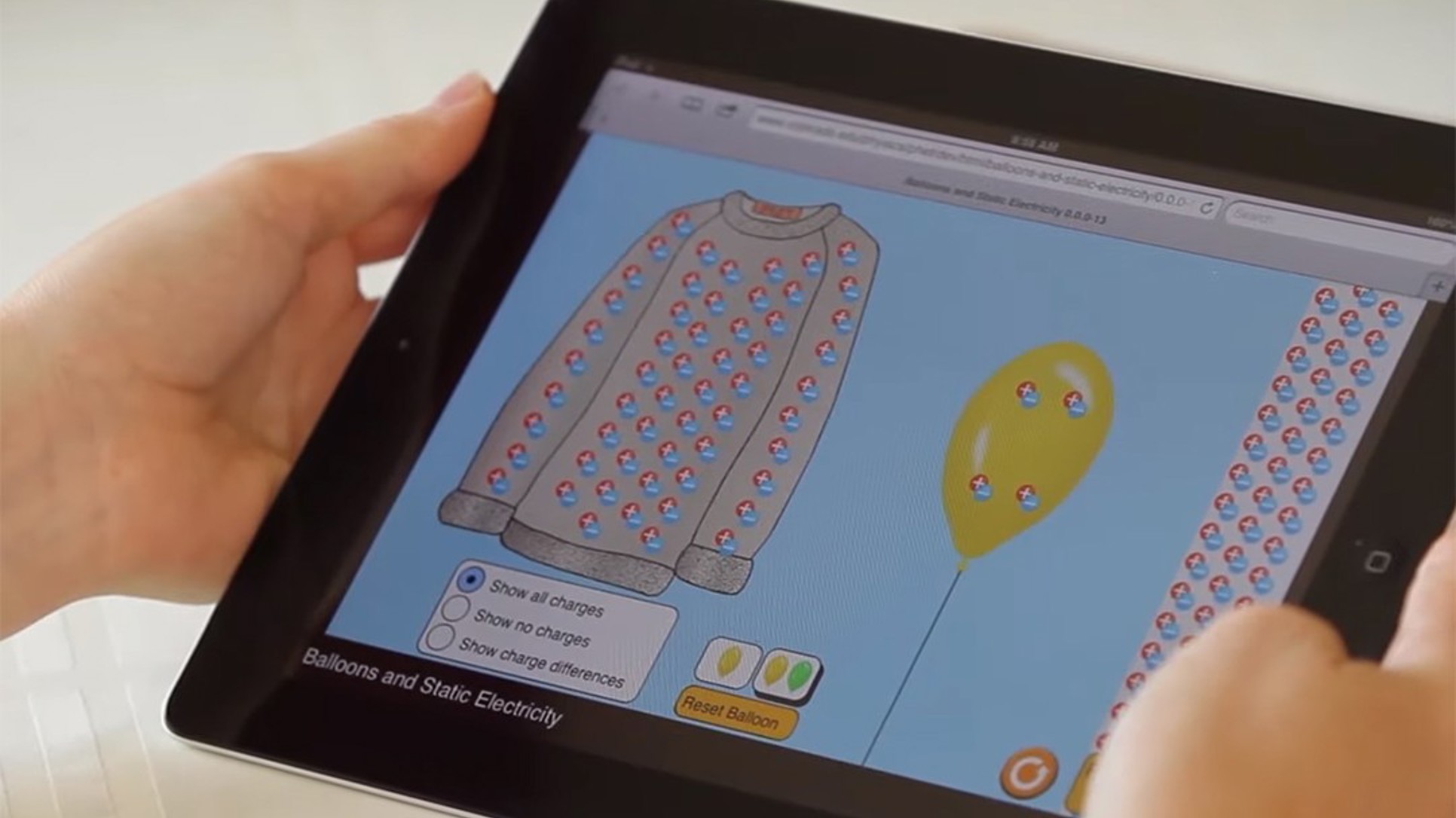

Indeed, the first thing that people have in mind when we talk about smart uses of data and digital technology in education is the personalisation of learning. How can we use technology to make learning more personal, more granular, more adaptive, more interactive?

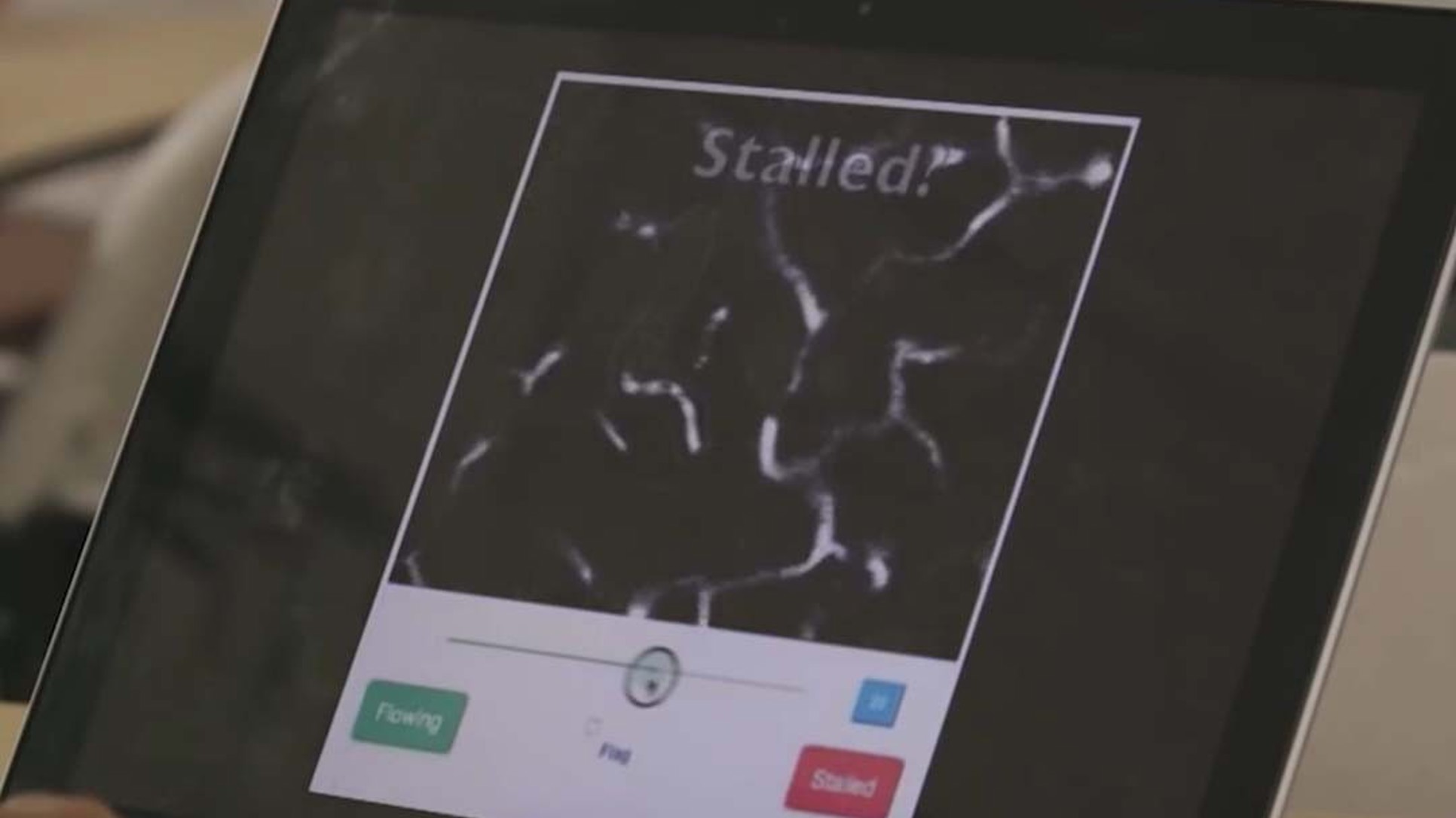

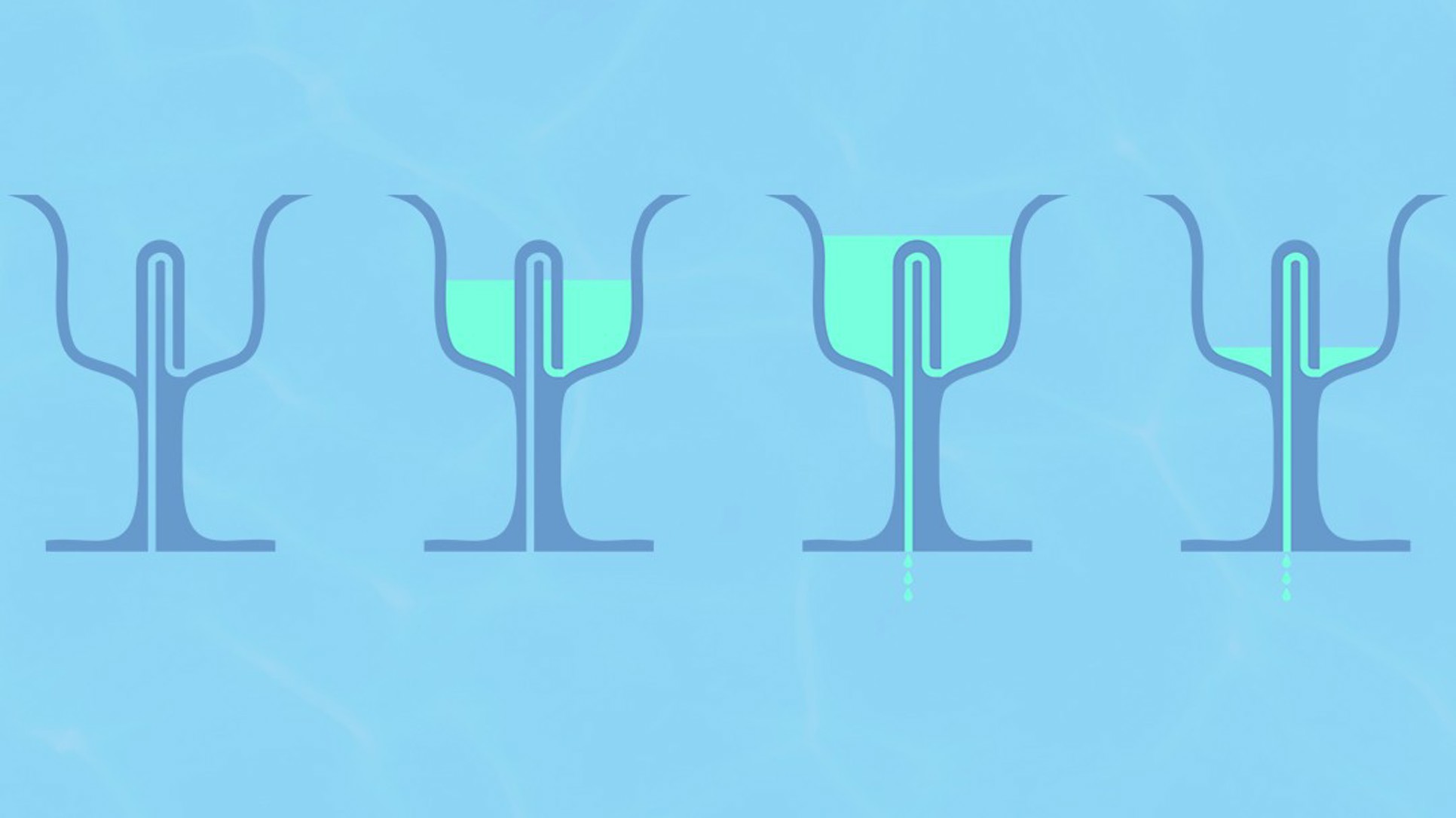

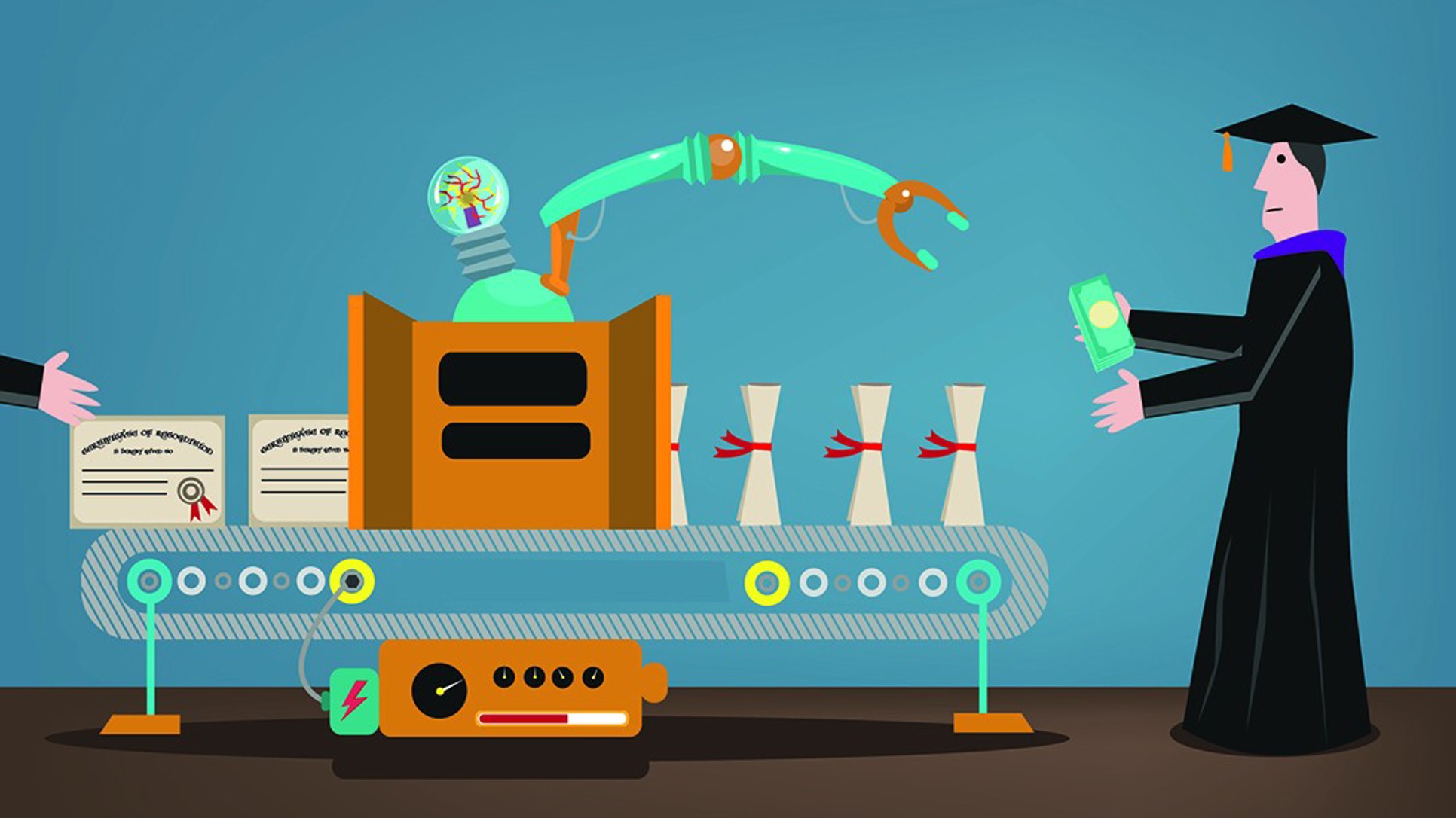

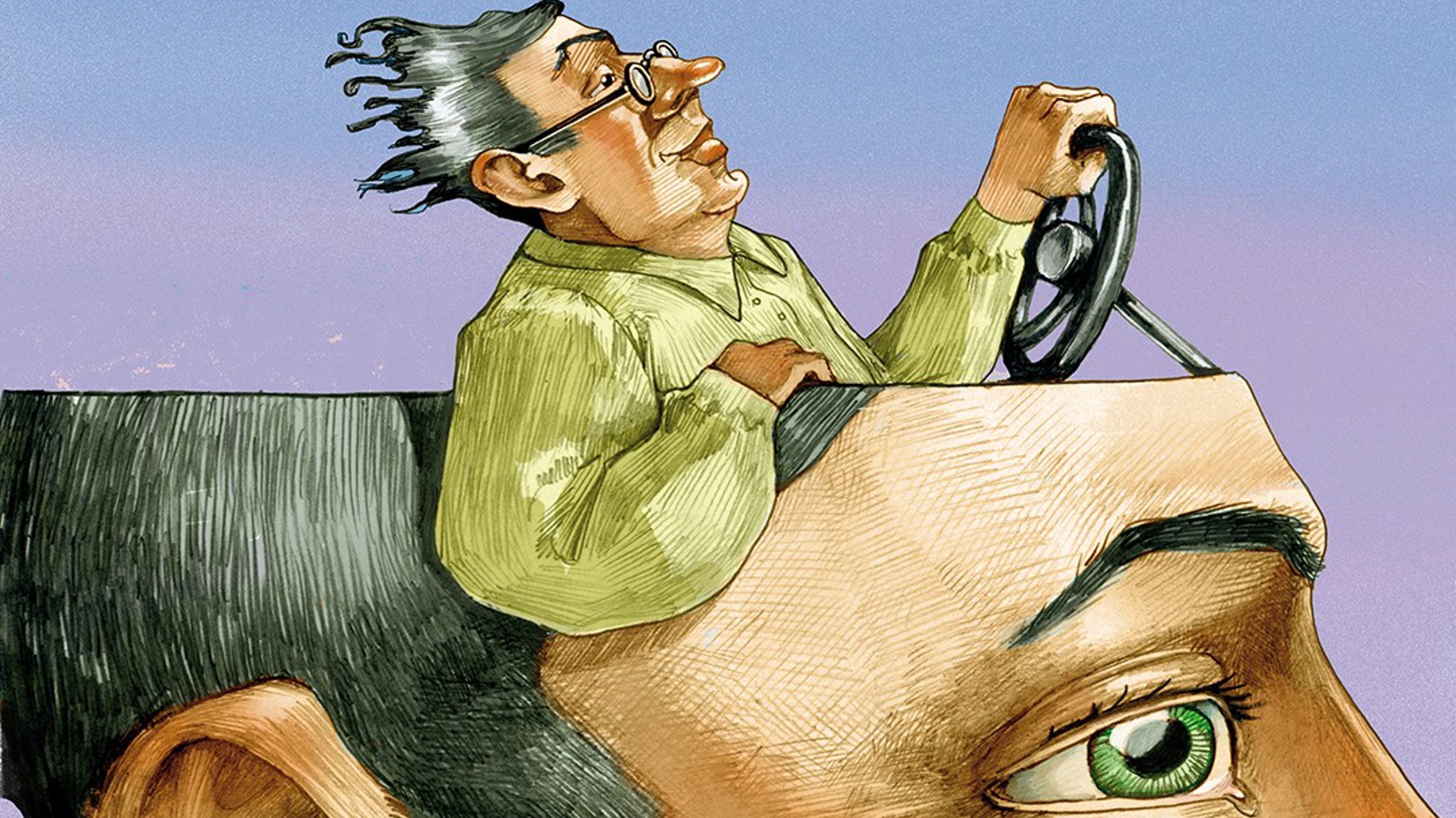

Our 2021 Digital Education Outlook has shown that there already exist interesting models that marry the strengths of humans and AI to better personalise learning. Think of a modern car: 1) technology first track the environment with sensors, then 2) diagnose risks on and off the road, and finally 3) determine appropriate actions to the driver – that a self-driving car would even take itself. In education, we are far from self-teaching class but such hybrid AI-human models can support teachers to 1) follow learners and track their environment, 2) diagnose learners and anticipate how they develop, and finally 3) determine the most appropriate actions to optimise learning.

This model is already applied at scale. Adaptive learning programmes are good at finding out how student progress, diagnose learning progression, identify the type of errors that they make, and then adjust their tasks accordingly. Such algorithms can provide detailed feedback at the step level, while a teacher could only report at a more macro level. And, in the same spirit, similar technology can then optimise learning at the curriculum level, by individually adjusting the order in which students work on different topics. Essentially, that can take us from one curriculum for all students, to getting the right curriculum for every student.

Of course, such technologies hold tremendous promise for educating student with special needs and disabilities, from the diagnosis up to the use of assistive features.

Is there any model of inclusion that is recognized as better than others and if there is - where, in which

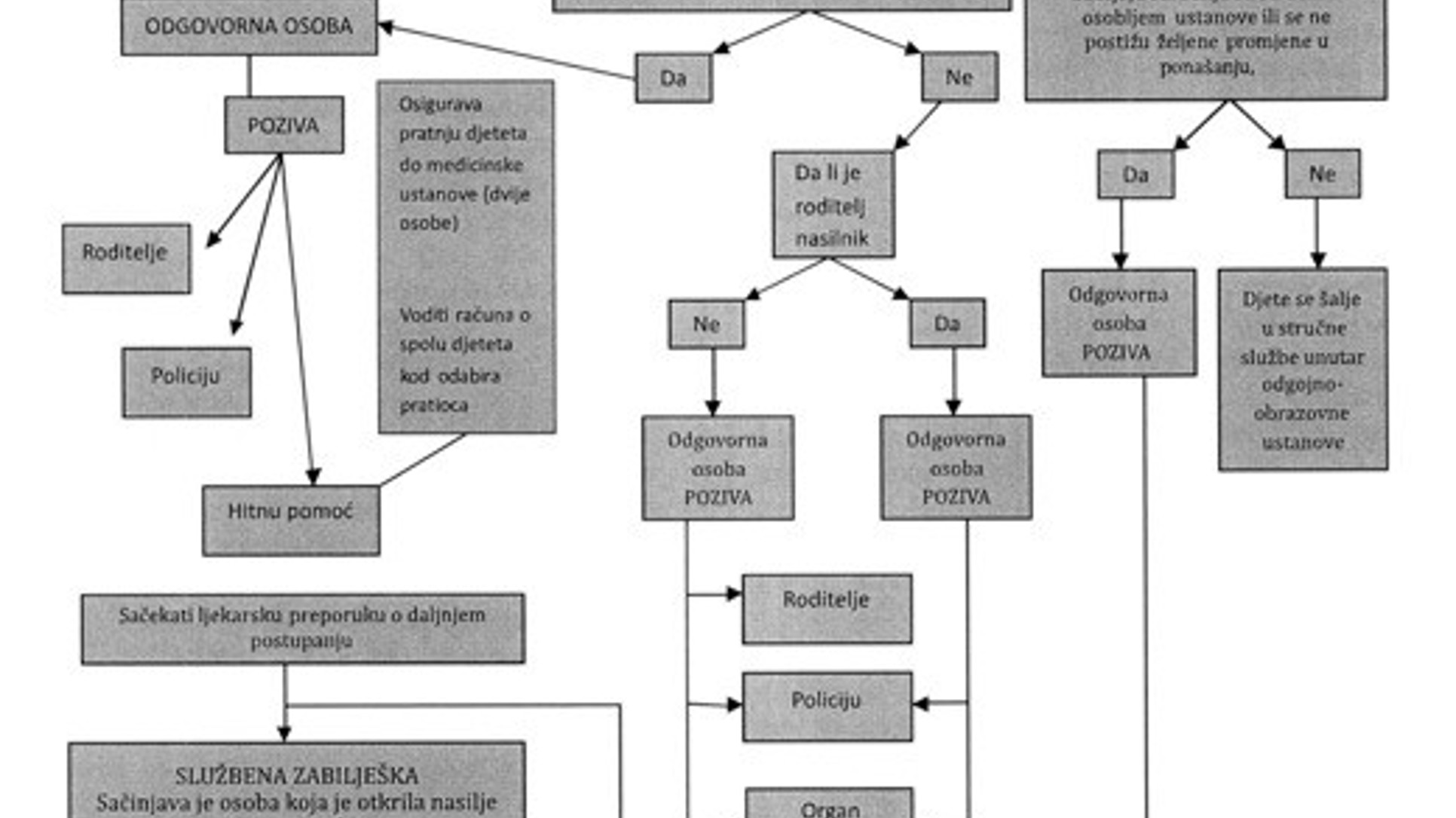

The OECD Strength Through Diversity team has conducted a mapping of policy approaches and practices for the inclusion of students with special education needs. Their analysis compares different models of special education needs (SEN) inclusion across countries. For instance, they identify the advantages and disadvantages of defining SEN at the international level or at the level of a country; of having more or less decentralised regulatory framework; of opting for special education settings or for mainstream schools; of input, throughput or output resourcing models; of including special education needs in teacher education, or promoting continuous professional development? Etc.

What emerge from this mapping is that a variety of governance arrangements, resourcing schemes, capacity-building strategies and school-level interventions coexist across and withing OECD countries to support the learning of students with SEN and their broader well-being. Each policy approach has diverse advantages and disadvantages that must be carefully taken into consideration when designing and implementing inclusive education policies.

How to wisely balance the schedule of investments in technology and in people?

Indeed, ultimately the policy challenge is to ensure that technology remains human-centred. To repeat the car analogy, in this sector you have technologies that assist the driver, that partially automate some decisions, or even that entirely take over commands in the case of self-driving cars – and probably for the best if we judge them on safety. But in education, where on that spectrum do we want to end up? We need to reflect carefully on what is the appropriate balance between the role of educators and technology, as learning is a social, relational, human process.

Our OECD Digital Education Outlook 2021 offers some principles to get this balance right. First, it argues that it is about keeping a human-centred vision, where digital technologies are deliberately and wholly designed with educators at the heart. Then, good investment demands a good understanding of the organizational, political, and technological factors that will shape the implementation of technology in the education system. This comes with the development of technical readiness, that is to say, making sure that the solutions we design are interoperable, connected, integrated and that they form an ecosystem. Finally, it is about developing staff readiness: the humans' capacities, the skills of teachers, by “shifting the culture” to promote a good use of technology. Hybrid human-machine systems will never replace teachers, but it can support teachers in reinventing themselves as designers of learning experience, as mentors, as coaches, as tutors, or as peers.

All of this requires a good strategic plan that sets out the short-term and the long-term wins; and it requires governments to take on a crucial role, with funding of course, but also by using public policy as a tool for shaping the ecosystem that provides enabling conditions for innovation to thrive.